Volume 2, Issue 53: Husbands and Wives

The summer after high school graduation is one of the more memorable periods in anyone's life, the final stretch where you are a child before you head out to the world to discover who you really are. (Or at least whom will you pretend to be for four years.) Some kids travel; some have one final high school fling; some just sit at home and stare at the wall until September comes and they get to leave.

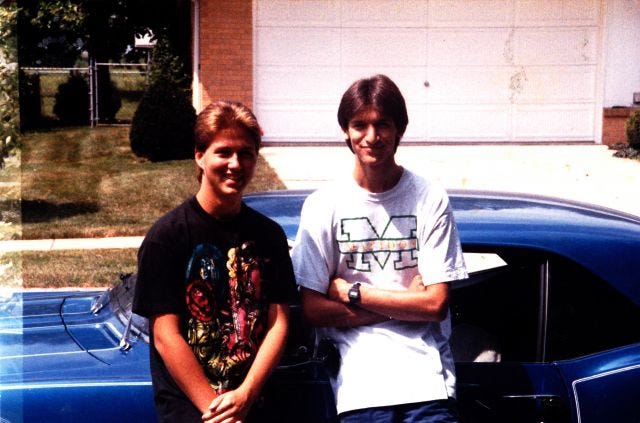

For me, it was the summer of 1993. My best friend Tim Grierson had learned in April that he had been accepted to the film school at the University of Southern California; I was going to the University of Illinois 45 miles up I-57. I'd be an entirely different, much worse person today had Tim not been my best friend in high school. In high school, in many ways, you are your friends; there were a ton of shitheads at Mattoon High School I could have been best friends with, and it was just my good fortune that I found the thoughtful kid who was as obsessed with movies and Kurt Cobain and the Cardinals as I was. (These people aren't easy to come across in rural IIllinois.) I'd hung out with Grierson every day for four years. That he would be moving 2,000 miles away in two months made me sadder than a 17-year-old could possibly articulate.

So we decided to have one last blowout. To send us off, to transition into the next phase of our lives, to best commemorate our friendship, to have an experience that we talked about forever ... we decided to have a film festival, just for us. We would go to the video store, come back with armfuls of movies, head back to my parents' place, sit in the den, and just watch every movie in a row, straight, no sleep, just the two of us watching a movie, talking about it, then watching the next one. It was a whole production. We told everyone we knew about it, we made my parents stay out of the den for the 30-hour stretch (my dad would walk through occasionally, shaking his head, bewildered by the strange boy who had grown up in his house), we even had friends come check up on us between movies to make sure we were still staying sane. It was the ideal way for us to, in our own way, say goodbye: To sit down and watch movies together, just us, the perfect commemoration of our friendship, a totally ludicrous experience that only the two of us would enjoy, a way of saying, "Yeah, we're moving 2,000 miles apart, and our worlds are about to explode, but we're always gonna be these two kids, together, forever." And we still are.

The film festival? Well. We went to the three video stores around town, to make sure we had all the specific movies we needed, and rented ... every Woody Allen movie. From What's Up, Tiger Lily to Husbands and Wives, the first Woody Allen movie either of us had seen in a theater and, perhaps not coincidentally, the one each of us considered the best Woody Allen movie. (I think Grierson has since amended this to Manhattan, and sometimes I flirt with Deconstructing Harry, but the general premise remains.) For two days, we watched every Woody Allen movie, in order. We loved the movies, but it was more than that: It was a way to mark ourselves as special, as different, Woody Allen serving as a bond between us that we'd always have. For years afterward, after every Woody Allen movie came out (and there was of course one every year), we would get on the phone, even if it was an expensive long-distance call, and talk about it for hours. The movies kept us close. Among all the friends we would make after high school, him in California, me in Champaign, St. Louis and ultimately New York City, they would all know us as The Woody Allen Fans. Any time he made a movie, everyone wanted to know what we thought of it. It was our thing. It was our original bond. The Woody Allen Film Festival. Will and Tim. We were proud of it. It was something we would always have.

That has changed.

************************

Woody Allen has not made a new movie since Wonder Wheel in December 2017, and it is possible we will never see another one. Amazon, which signed a four-picture, $68 million deal with Allen in August 2017, has refused to release A Rainy Day in New York, starring Timothee Chalamet, Selena Gomez, Elle Fanning, Rebecca Hall and Jude Law, and Allen is currently suing Amazon for breach of contract. He recently signed a deal with Spanish film company Mediapro to make his next film, but the details are hazy and the Amazon lawsuit could end up engulfing everything. It may not matter anyway: The number of actors who now proclaim they will never work with Allen again is massive -- including Michael Caine and Mira Sorvino, who both won Oscars in Allen films -- and the three primary stars of A Rainy Day in New York all say they hope the film doesn't come out and have donated their entire salaries for the film to RAINN. I bet we never see another Woody Allen movie.

Woody Allen has been one of the singular organizing principles of my life, not just a foundation of my friendship with Grierson, but a guiding force for me as a writer. I have always admired his philosophy of writing, which is just to work constantly, keep creating things and putting them out into the world, and not getting too attached to anything. You make something, you show it to people, then you go out and you make something else. Sometimes you'll make something good, sometimes you won't, sometimes people will love it, sometimes people will hate it, but you just gotta keep making shit regardless. All feedback, positive or negative, is the same, because the toughest critic is always yourself; you can't believe the good reviews any more than you can believe the bad ones. When in doubt, just write some more. In the end, it's all just work. Woody Allen's approach to writing is one I actively have attempted to emulate, to this day.

But I really don't care if I ever see another Woody Allen movie. And if one does come out, I won't watch it.

I never really thought about Dylan Farrow's allegation that Woody Allen molested her as a little girl until recently, until the dawn of the #MeToo movement, and I suspect you didn't either. I didn't think about it when it first surfaced in the wake of the explosive split between Allen and Mia Farrow after he began dating Farrow's adopted daughter Soon-Yi Previn. (With whom Allen has now been for nearly 30 years.) I didn't think about when Mia Farrow alleged it in her autobiography in 1997, or when she brought it back up in 2013. I didn't think about it when Dylan Farrow wrote about it for the first time herself in 2014. I should have. But I didn't. I continued to watch his films, and write about his films, and obsessively chronicle every dumb thing he made, until, inevitably, Allen and the #MeToo movement intersected with Dylan Farrow's December 2017 Los Angeles Times op-ed, "Why has the #MeToo revolution spared Woody Allen?" At that point, I, and everybody else, could no longer ignore it. None of us should have in the first place.

I do not know if the allegation is true. Dylan Farrow's claims are harrowing and compelling. But this is a messy, ugly case (and, unlike Bill Cosby's or Kevin Spacey's cases, is not something that has multiple other allegations to make the evidence overwhelming). Dylan Farrow's brother Moses claims that the incident never happened and has some truly disturbing allegations about Mia Farrow, including that she regularly beat her children and that his sister Tam killed herself because of Mia's abuse. I don't know if that is true either. But this is an ongoing, seemingly bottomless pit of family strife and raw emotion, all in constant battle in the public square for several decades now. The character witnesses tend to line up more to Mia Farrow's side -- that Ronan Farrow was, amazingly, become one of the most respected investigative journalists of his generation and has fought Moses' allegations certainly bears considerable weight -- but the idea that this thing has sides at all, with parts of the family on one side and other parts of the family on the other, makes it particularly unseemly: Like most family fights, it feels like none of my business. I want to stay out of it. I've tried to.

But -- and this is one of the central questions of ethical cultural consumption in this era -- does watching Woody Allen movies make it my business? Is caring about Woody Allen movies taking a side? Is claiming that I don't know anything about that family so I'll stay out of it take a side? I think it does.

In Dylan Farrow's essay, she writes, "Woody Allen is a living testament to the way our society fails the survivors of sexual assault and abuse. So imagine your seven-year-old daughter being led into an attic by Woody Allen. Imagine she spends a lifetime stricken with nausea at the mention of his name. Imagine a world that celebrates her tormenter. Are you imagining that? Now, what’s your favorite Woody Allen movie?" I find it difficult to read that and justify having anything to do with anything that man does at all. I feel shame and embarrassment that I ever cared so much in the first place. And that previous paragraph, this "hey, I'm staying out of it, gotta hear both sides," is ridiculous and harmful, supporting the idea that making up molestation allegations is somehow this commonplace occurrence. Aaron Bady wrote, in an excellent essay in The New Inquiry back in 2014, that "His presumption of innocence can only be built on the presumption that her words have no credibility, independent of other (real) evidence, which is to say, the presumption that her words are not evidence. If you want to vigorously claim ignorance -- to assert that we can never know what happened, in that attic -- then you must ground that lack of knowledge in the presumption that what she has said doesn’t count, and we cannot believe her story."

Bady was right then. I just wasn't listening.

Bady also notes that, because this is not a court of law, he doesn't necessarily have to be right: Lambasting Allen and pointing out the allegations every time he makes a movie is not in fact sentencing him to prison. "It’s a good thing, generally, that juries are empowered to say 'We think the accused is probably guilty, but we’re not sure beyond a reasonable doubt, so we will not convict,'" Bady writes. "That bar is set high for a reason; if you’re going to lock a person in a cage for a long time, you need to be really sure. But we are also empowered to say the same thing. We are also empowered to say 'We think Woody Allen probably molested a seven year old.' And because we are not in a court of law, we don’t even need to say the second part. The fact that we will not convict him doesn’t even need to be implied. He is not, after all, on trial."

And that's where I've landed. Woody Allen is not my friend. There have been various celebrity "defenders" of Allen in the recent years, from Penelope Cruz to Alec Baldwin to Diane Keaton. But my consumption of Woody Allen's films, and my adaptation of some of his working habits, does not mean I have a personal connection to him. I don't. His work is a part of my life, but it's mine, not his. A few years ago, I wrote about the Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa home run chase for The New York Times, making the argument that just because the two of them were using performance-enhancing drugs the whole time doesn't mean the joy you took from watching them somehow disappeared, like it didn't happen or something. That Woody Allen may be a monster doesn't mean that his movies didn't still mean something to me and millions of other people. But it doesn't mean he's not a monster either.

When you create something, you put it out into the world, and then it belongs to everyone else. I can do with Woody Allen's work what I wish. The person is irrelevant. This is often used to defend artists on moral grounds; Picasso was an asshole, but the work is genius. But this goes the other way too. I can embrace the work, I can reject the work, but I can do it for whatever reasons I want. Picasso is an asshole either way. If I decide the quality of the work does not outweigh the shittiness of the man who made it -- or the hurt that it causes other people, other victims, to defend the man publicly, to not shun him, to pretend it's all OK because it didn't happen to anyone I know -- then the quality of the work becomes irrelevant. Then it doesn't matter whether it's good or not. If watching something for my own enjoyment becomes unpleasant because of the harm it causes other people, well, it's not very enjoyable then anymore, is it? We do not consume culture in a vacuum.

So I am out. I cannot support Woody Allen, or his films, or his work, any longer. These newsletters have been named for Woody Allen movie titles for the last year, because he has been a huge part of my professional and cultural life, specifically building up to this edition, when I promised I'd finally reckon with this. So this is my minor, pointless, personal reckoning: I don't want to watch Woody Allen movies anymore, and I hope he never makes any more of them. A large part of the conversation of the last year-plus has been realizing when it's time to shut up, when it's time to listen, when it's time to make a decision about things you once loved but were causing more harm than good. So this is my decision.

******************

When Grierson came to visit me for the first time in New York City, back in 2002, we knew exactly what our first stop would be: The Cafe Carlyle, where Woody Allen had been playing clarinet with his jazz band for 30 years. We sat in the audience, rapt, seeing Allen in person for the first time in our lives. He was older, frailer than we realized. He was 66 then. He's 83 now.

I don't remember much about the show except that we went to it. But I remember the rest of that trip vividly, from Grierson crashing on my couch to him getting lost trying to get back to my place after a dinner to us constantly hanging out at the bar downstairs from my apartment because I didn't have air conditioning and the bar did. Seeing Woody Allen play was the excuse for the trip, but it was not the reason for it. Tim wasn't there to see Woody Allen. He was there to see me. We had a blast.

And that's all that matters. Woody Allen's work is a part of my history, but it is my history, not his. And I can choose not to make him part of my future. My life was my own with Woody Allen movies in it. It will be still be my own without them.

Here is a numerical breakdown of all the things I wrote this week, in order of what I believe to be their quality. You may disagree. It is your wont.

1. The Craziest On-Pace-For Stats of Baseball's First Week, MLB.com. I cannot get enough baseball right now, even with the Cardinals off to a slow start. (Not as slow as the Cubs', though!)

2. Data Decade: Best Second Basemen of the Decade, MLB.com. This series is coming along well, I think.

3. First Impressions From MLB's First Week, MLB.com. My MLB.tv is getting a serious workout.

4. The Age of the Old Athlete Is Over, New York. Sometimes I maybe get a little too 50,000-feet up.

5. Stephen King Adaptations, Ranked, Vulture. Grierson added Pet Semetary to this list, but I haven't seen it yet, so this is his view and his view only.

6. Pivotal Seasons For Particularly Noteworthy Players, MLB.com. All Chris Davis, all the time.

7. Debate Club: Best Post-Batman Tim Burton Movies, SYFY Wire. There are a few halfway decent ones.

THE WILL LEITCH SHOW

This week's was the great Jemele Hill. Plus, we have a remote bit where I go to the Queens Baseball Convention. Watch on Amazon or on SI TV.

PODCASTS

Grierson & Leitch, on "Dumbo," "The Highwaymen" and "The Beach Bum."

Seeing Red, Bernie and I try to figure out the first week.

Waitin' Since Last Saturday, no show this week.

GET THIS LUNATIC OUT OF HERE 2020 PRESIDENTIAL POWER RANKINGS

I'll confess to not knowing much about Rep. Tim Ryan, who announced his candidacy this week, but I have to say: He's the most Republican-looking Democrat I've ever seen. He totally looks like the fifth guy Trump tried to make Attorney General.

1. Kamala Harris

2. Elizabeth Warren

3. Beto O'Rourke

4. Pete Buttigieg

5. Cory Booker

6. Kirsten Gillibrand

7. Julian Castro

8. Amy Klobuchar

9. Jay Inslee

10. Bernie Sanders

11. John Hickenlooper

12. John Delaney

13. Tim Ryan

14. Wayne Messam

15. Andrew Yang

16. William Weld

17. Marianne Williamson

18. Tulsi Gabbard

ONGOING LETTER-WRITING PROJECT!

I'm in Minneapolis right now, and I met with a frequent letter-writer for a beverage last night. Amusingly, I tried to schedule the entire meet-up through the mail. (He eventually just texted me.) Write me!

Will Leitch

P.O. Box 48

Athens GA 30603

CURRENTLY LISTENING TO

"Carry the Zero,' Built to Spill. Built to Spill is another of those bands I discovered way too late but have gotten sort of obsessed with. I'm really into "Keep It Like a Secret," just in time for the band to do a tour in honor of its 20th anniversary, which sounds about right.

Get out there and ball, kids.

Best,

Will