My professional and personal life divides up rather neatly between two eras: Before Deadspin, and After Deadspin.

I was always an ambitious kid. I learned to read when I was three and used to get trouble in first grade for skipping ahead on the Letter People. In grade school, I created a weekly newspaper full of sports scores called “The Will Street Journal,” and in junior high I wrote countless short stories, usually about girls or Guns ‘n' Roses or both, on one of those old word processing typewriters that had a one-line screen where you could see your words, and when you were done, you’d hit Command-Print and the whole thing would just come out. I think it was this exact model.

In high school I wrote for the local town newspaper, the Mattoon Journal-Gazette, played baseball and scholastic bowl and acted in every school play, and when the school principal told me there was no student paper, Grierson and I went out and started our own. In college I lived at the student newspaper (earning my first weekly column by the end of my freshman year), wrote for countless publications throughout northern and central Illinois and became friends with Roger Ebert. I developed a reputation as a kid who was Going Somewhere, and I fostered and cultured it: It made me feel special to be in a hurry, a hurry to get out of Mattoon, a hurry to make a big name for himself, a hurry to be an Important Writer. I was young and hungry and reckless and desperate to be seen and heard.

And then I moved to New York in 2000, as every young Writer In A Hurry someday must, and it all just stopped. The dot-com I worked for collapsed. The full-time writing gigs never materialized. The freelance gigs vanished. There was not, in fact, a series of publishers lining up to publish my Great American Novel, which was right there, right there in my head, I just have to get it to paper, gotta get it down, just need somebody to give me a chance. I had no job, no money, no prospects and, for a hairy six-month stretch or so, no place to live. (Do kids couch surf anymore? I think in one three month stretch I slept on eight different couches.) For five years, my career was non-existent. I took a series of temp jobs, from licking envelopes for a theater company to hauling boxes of T-shirts on hand trucks around Manhattan, and spent nearly two years answering phones at a doctor’s office at Mount Sinai on the Upper East Side. I still wrote all the time, and we founded The Black Table during this period, but that doomed art project, as thrilling as it was, further exacerbated the problem: It was something we had to create to pour our energy into because no one would hire us to pour it into anything else. It became one more hill to die on.

At one point, about three years into my repeatedly failing New York City adventure, my father, who has always been supportive of my career and work without ever fully understanding it (which might just be one of the most important things a parent can do), called me and said there was an opening for a public relations person at the St. Louis office of Ameren, the power conglomerate that had bought CIPS, the place he’d worked as a substation electrician for two decades. Dad had no in at this job, but he saw it on some internal board, knew that his son—whom he’d paid for four years of college and whom he’d always thought ticketed for big things but now was answering phones at a doctor’s office in some strange city halfway across the country for some reason—needed a steady job and read that the job required “writing skills.”

“I thought you might want to look into this? Can’t hurt.”

It was the first time my father had ever recommended a job to me, had ever even implied he didn’t think things were going well out in New York, and it was deeply alarming: They’re scared it’s not going to work out for me. And why wouldn’t they be? I was 29 years old, working thankless jobs for no money in the most expensive city in the country, and the only thing I was excited about was working for hours every day for free on a website I did with my friends that had no readers. If my parents were this concerned, surely, everyone was. Will had all this promise. We loved that he always dreamed big. But he’s almost 30 years old now. It’s probably time for him to start getting serious about his life. It was becoming increasingly clear they weren’t wrong. How much longer could I continue to kid myself? (I politely declined Dad’s invitation and have never brought it up again until right now.)

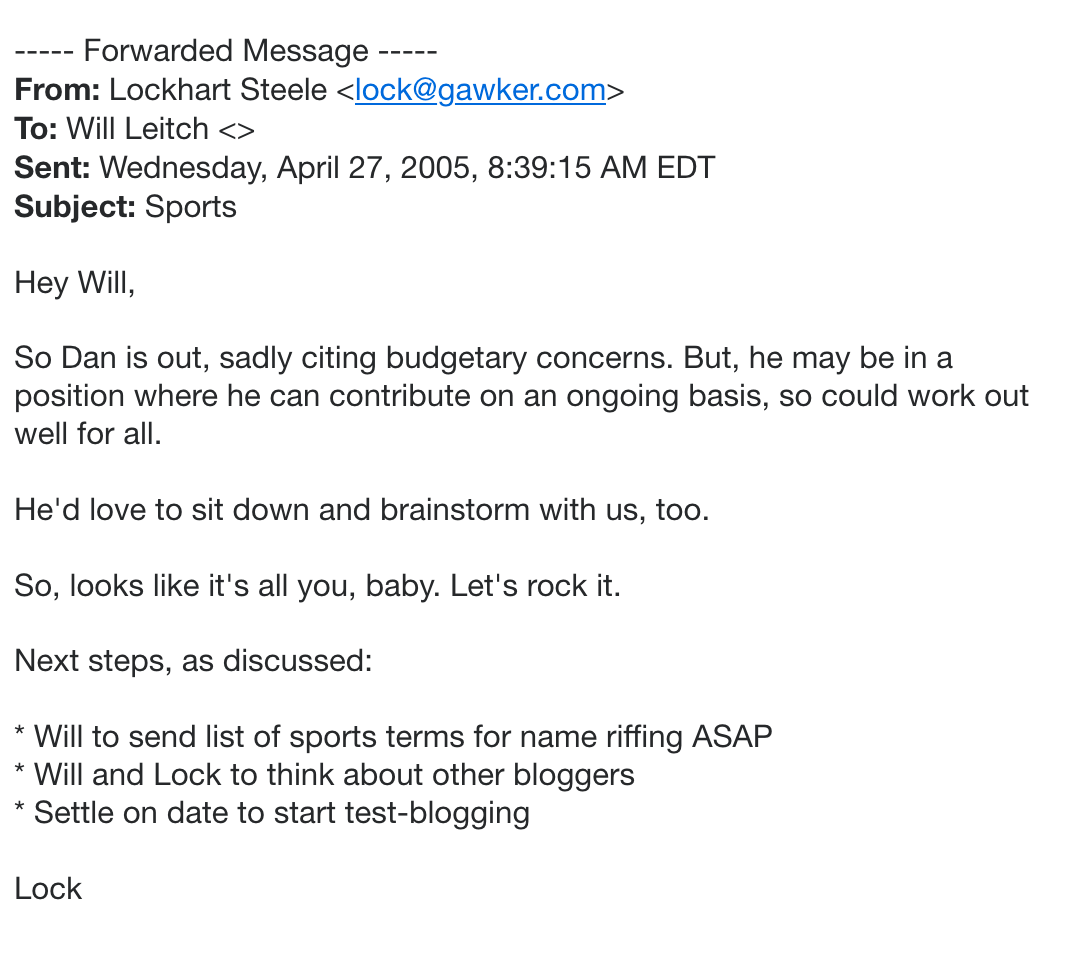

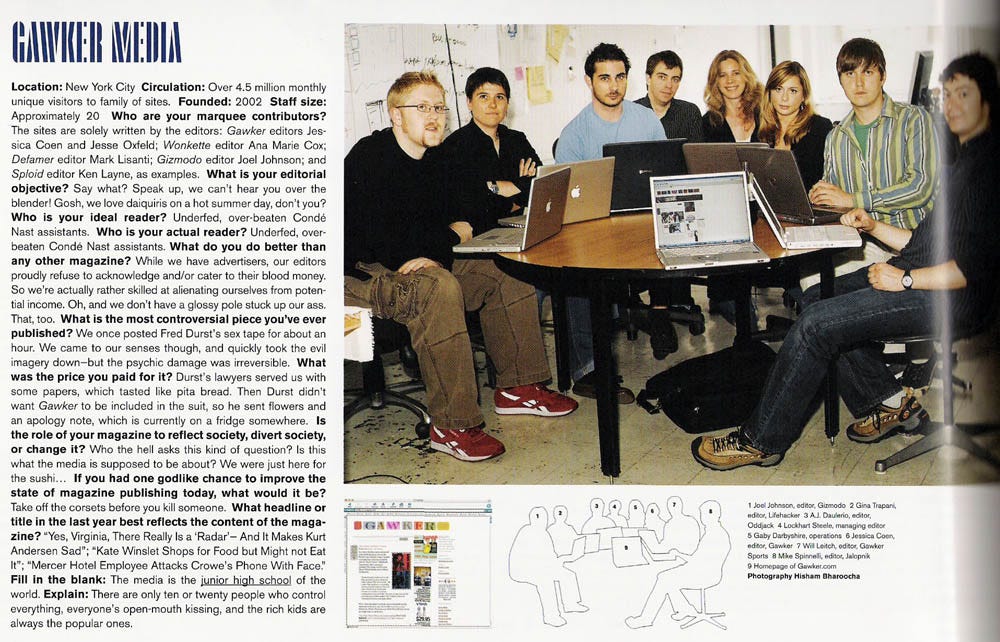

Then Deadspin happened. It was early 2005, and I’d gotten to know Lockhart Steele, who was the managing editor of Gawker Media, and, based off the work I’d done at The Black Table, he offered me a job writing for a gambling blog called Oddjack. I told him that I was morally opposed to sports gambling—it is bad for the soul even before you go broke doing it—so I would be a terrible editor of a gambling site, but I, as they might say today, decided to shoot my shot and wrote a long memo to him pitching a sports site. (He said I probably shouldn’t bother. Some guy had tried to do a sports site for them a year before but he was pretty terrible and it had mostly soured Nick Denton on the idea entirely. Sports blog historians will enjoy noting that that person was Jason McIntyre.) Lockhart apparently still has the memo I wrote somewhere, and I honestly don’t remember much of it, but it must have been convincing enough, because they decided to do the site right then and there. Because I was a nobody, they wanted someone else to run the site I’d just pitched them and have them make me their assistant, but after everybody with a name (including Bill Simmons, Jonah Keri and Dan Shanoff) turned them down, they let me go ahead and just do it the way I wanted. I was cheap, after all.

I did not imagine the site was going to last long. Gawker Media sites rarely did. I figured I’d write the shit out of everything for three months, hopefully make a little bit of a splash and get my name out there a little bit, and if I caught a break, maybe a few editors at New York or Details or something would let me write for them once they inevitably shut this site down. The day the site launched, on September 8, 2005, nearly one month before my 30th birthday. I emailed the URL to all my friends and family, begging them to read it. I’m sure they thought it was another one of Will’s hare-brained ideas; isn’t he getting a little old for this?

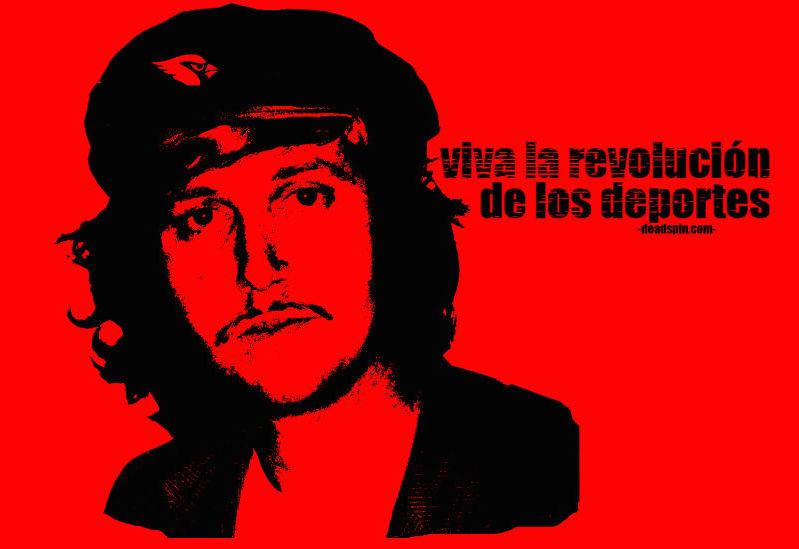

And then the site took off. You know what happened with the site after that. In many ways, I’m fortunate I had failed so much before Deadspin happened: I knew quickly that this was as close as I was going to get to a big break, and therefore I was mature and determined enough to make sure I didn’t screw it up. (If I had been 22 or so, I wouldn’t have understood how rare such opportunities are.) I dedicated my entire life to Deadspin. I would work 16 hours a day on that site, agonizing over every word, over every story placement, over every photo, over every headline, over every comment. I had spent my entire life telling myself I would make something lasting and important, and then here this was, this thing that was popular and different and entirely mine. People still tell stories of all the wild partying that was going on at Gawker Media during this time, but I’m never a part of any of them. I was in a hurry. I wanted to work on that site all day and all night, every day and every night. It became all I cared about. I lost friendships, I had serious relationships end, I went whole weeks without seeing anyone because I had to make sure that this worked, that this thing I had been waiting for, this gift that had fallen out of the sky, didn’t go away. This is what I’d been working for. This was what was going to justify all of it. This was what I left Mattoon for. I couldn’t blow it.

And god I loved it. I lived and breathed Deadspin. I now know when people look back at that time, they see it as some free-wheeling, chaotic, wild jamboree, but I was obsessive and calculating. I never looked at traffic numbers, but I knew the site was getting more well-read and more influential. This just made me hold on tighter. People always called the site “snarky,” but it never felt that way to me. I considered it entirely, almost painfully, earnest in every way. It was my shot. At one point, someone asked me what I wanted to do after Deadspin. I told them, “Nothing. I want to die at my computer writing Deadspin.”

This is, suffice to say, not an attitude that leads to positive long-term health, and it of course could not last. I never got burned out on doing Deadspin—just like I never get burned out on writing now—but I could see parts of the business I had no interest in (advertising rates, search engine optimization, traffic leaderboards, integration and synergy and all sorts of those other nonsense words) starting to creep in around the edges. I knew I wouldn’t be able to stave off the barbarians forever. So when Adam Moss offered me a job at New York magazine, then as now one of my favorite magazines in the world, I thought it would be a smart time to leave. I knew if I didn’t let go, I’d grip the reigns so tightly that it would lose what made the site special to me. I didn’t want to be an entrepreneur. I just wanted to write. I had grown too close to Deadspin, and I wasn’t interested in the cult of personality that the internet has a tendency to help fester: By the end of my run, I would write a post about anything, not even a good one, and the first few comments would all be some variation of “yeah! that’s awesome! Go get ‘em, Will!” Stay in that environment too long, you’ll turn into a sociopath. I needed to move on before it killed me. Besides: It’s never a bad idea to leave when people still like you. Because rarely do people like you.

So I left. It has been more than 11 years since I left. Since I left, Deadspin has exploded, become even more massive and vital than I ever could have imagined. Every editor since me, from A.J. Daulerio to Tommy Craggs to Tim Marchman to Megan Greenwell to Barry Petchesky (to Dave McKenna!), put their own spin on the job, but all of them made it bigger and better. It was always disorienting to me when people would claim that the site had somehow gotten worse since I left: This was so plainly untrue that it was comical. The number of incredible people who have written for Deadspin blows my mind to this day. Jia Tolentino wrote for Deadspin! Charlie Pierce wrote for Deadspin! Tom Scocca worked for Deadspin! The scope of Deadspin in 2019 was so much more vast and ambitious than my meager brain could have ever conceived. It was smart, it was funny, and it was important. And it had so many different and exciting voices than a dopey Midwestern white guy who wouldn’t stop writing about Rick Ankiel and Woody Allen movies. I stopped being a person who had anything to do with Deadspin anymore, save for my annual end-of-year column, and just became a devoted fan. Deadspin evolved into, in all seriousness, one of the most compelling websites in the entire goddamned world.

It of course couldn’t last. This last week, to see what these ghouls have done to Deadspin, has been distressing and exhausting and infuriating and, yeah, ultimately downright inspiring. Deadspin has always been its own island in an ocean raging out of control. The site was hugely popular and was the rare site that actually made a profit, but in the world of media, that never has anything to do with anything. The Hulk Hogan/Peter Thiel lawsuit pried it away from Gawker, which led to it being owned by Univision, which had money issues elsewhere and thus had to sell it to a venal private equity firm, who hired a unique gaggle of dipshits who were constitutionally dedicated to stepping on their own dicks. (It is difficult to destroy a beloved website in six months, which is how long it has been since Great Hill Partners bought the place, even if you are steadfastly trying. Yet here we are.) What happened this week, considering the way that staff was treated, was inevitable: There are newsrooms out there you can jerk around and screw with and get them to roll over, but Deadspin’s was never, ever going to be one of them. That staff went out fighting. They went out like warriors.

And now it’s gone. (And it’s gone. Do not ever look at the desiccated corpse roaming around over there and consider it anything resembling Deadspin.) It is much easier for me to deal with it being gone than it is for the staff that just left. It is theirs far, far more than it is mine. For years, in fact, I have been benefiting from their hard work: The better they made the site, the better “founder of Deadspin” looked in my bio, even though I had nothing to do with how good they were. I am used to seeing the thing I poured my blood into run by other people. It’s easier for me in that regard too: I got to see smart, qualified people turn it into something better. They will have no such good fortune.

It sucks. It sucks as a founder, it sucks as a journalist, it sucks as a reader, it sucks as a sports fan. It’s all so pointless and dumb.

But we’re still all so lucky. We’re lucky that a place like Deadspin existed. I’m lucky that we lived in a time that I got to shape it into what it was, and other people got to expand on that and make it so much more. I don’t know what would have happened had Deadspin never come along in my life. To hear the stories of people this week who had the same experience, people who said they found a community through Deadspin, or met their spouses through Deadspin, or needed Deadspin to get them during a particularly difficult time in their life, has been deeply moving. I was at a soccer game in Atlanta on Wednesday, and two guys recognized me at the bar, came up to me and said, “we’re really sorry about what’s happening over at Deadspin. That site has been a part of our lives for years.” We’re all a part of that community. That will always be what matters, even if those ghouls will never understand it.

I can honestly say that Deadspin saved my life. I would not be me without it. Everything I’ve ever done in my career over the last 11 years has been a direct result of my founding of Deadspin. It was the pivot point in my life, what led to everything I have now and everything I will have going forward, both professionally and personally. It was my lucky break. For the last 11 years, it has just been a site I have loved to read and honored, even if unfairly, to get to be associated with. No matter what I do the rest of my life, it will be in the first paragraph of my obituary. I have that staff to thank for that. I’m just so lucky to have gotten to be a small part of it. Whenever you lose something you care passionately about, there is grief, and there is pain. But ultimately you just feel grateful. You feel grateful you ever got to be a part of something so wonderful in the first place.

I miss the site already. I am certain I always will.

Here is a numerical breakdown of all the things I wrote this week, in order of what I believe to be their quality. You may disagree. It is your wont.

The Wisdom of the Crowd, New York. This piece about Nationals fans booing Donald Trump serves as an excellent delivery device for many of my thoughts about both sports fandom and politics.

Martin Scorsese Movies, Ranked, Vulture. Grierson and I were very honored they asked us to do the definitive Scorsese rankings, and we were both delighted by how it turned out.

Data Decade: Best Free Agent Signings of the Decade, MLB.com. This series is now back and bi-weekly again.

Edward Norton Movies, Ranked, Vulture. We had a lot of these big lists due in a short amount of time.

Reasons the Nationals Should Still Have Hope, MLB.com. Written right after Game Five .. it doesn’t look so bad right now!

Flags Fly Forever for Nationals, MLB.com. My series postgamer.

What’s at Stake in Game Seven of the World Series, MLB.com. So many sports stories get so irrelevant so soon.

Debate Club: Best Terminator Villains (Who Aren’t The Terminator), SYFY Wire. Terminator 3 was good, honest.

The Thirty: How Every Team’s Big Free Agent Signing Turned Out, MLB.com. Not bad, actually!

PODCASTS

Grierson & Leitch, our yearly mailbag show! We answered a bunch of questions, and then talked about Dolemite Is My Name and The Current War.

Waitin' Since Last Saturday, we reviewed the Kentucky game, and I spoke with The Athletic beat writer Seth Emerson about Georgia at midseason.

Seeing Red, no show this week.

GET THIS LUNATIC OUT OF HERE 2020 POWER RANKINGS

Well … that didn’t go well. I do not believe this is the last we have heard of Beto O’Rourke. But I perhaps think it best that this be the last we hear from him for a while.

And: This was such an insane week that this didn’t even make the top 10 of weird-ass things to happen this week.

1. Elizabeth Warren

2. Cory Booker

3. Joe Biden

4. Bernie Sanders

5. Amy Klobuchar

6. Pete Buttigieg

7. Kamala Harris

8. Michael Bennet

9. Julian Castro

10. Steve Bullock

11. Andrew Yang

12. Tom Steyer

13. Mark Sanford

14. William Weld

15. John Delaney

16. Marianne Williamson

17. Tulsi Gabbard

18. Joe Walsh

ONGOING LETTER-WRITING PROJECT!

Turned in another draft on the book this week, so we can start getting in a regular rhythm on these again. So keep ‘em coming!

Will Leitch

P.O. Box 48

Athens GA 30603

CURRENTLY LISTENING TO

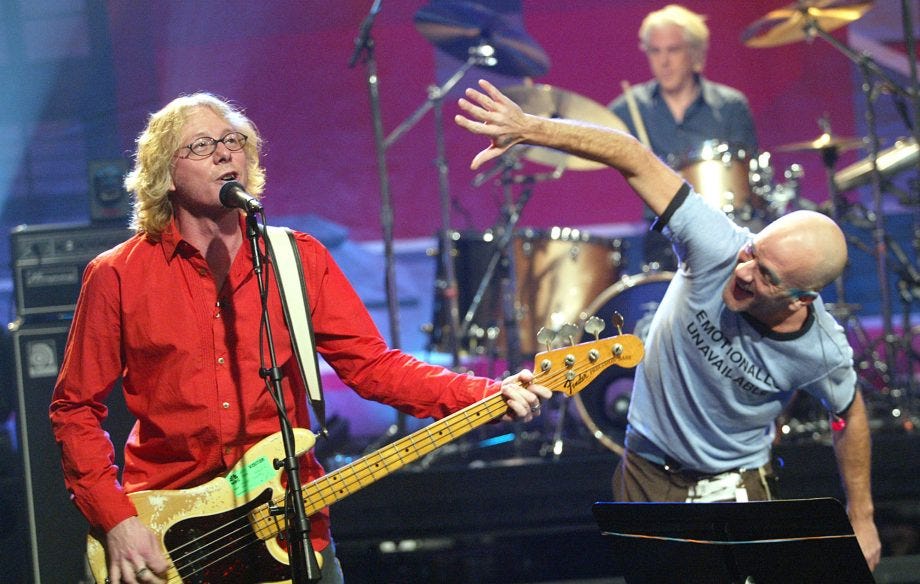

“What’s the Frequency, Kenneth?” R.E.M. It’s the 25th anniversary of R.E.M.’s “Monster” album—also, whoa—and they have a big anniversary remix. It sounds … strange! Not bad, exactly, just so different that I can’t really wrap my mind around it. Anyway, “Monster” is an underappreciated R.E.M. album, and every single one of those songs holds up no matter how they’re mixed.

Happy Halloween, beep beep.

Have a good weekend, all.

Best,

Will