Here is a button where you can subscribe to this newsletter now, if you have not previously done so. I do hope that you enjoy it.

Every writer, or at least every writer with a modicum of self-awareness (which is definitely not “every writer”), reaches the point where they realize that they are not in fact the genius and a visionary they had convinced themselves they were. I’d argue it’s normal, even healthy, for every young writer to believe they are God’s gift to prose when they are just starting out, to rue every editor who dares change even a syllable of their beautiful words, to believe that the only reason they aren’t atop the bestseller lists and writing deep-dive features for the New Yorker is because the world wasn’t ready for them, that they’re ahead of their time, that the deck is stacked against them. You need to think that you are uniquely talented, better than everyone, really, to have the stupid gumption to get into this business in the first place. And it’s just as important to have that knocked out of you—so that you can stay in this business.

There are plenty of different ways to have that Awakening, that understanding that being a writer is not like being a pitching phenom, as if you were just blessed with a lightning bolt howitzer of an arm and merely stepping out on the field will make everyone cow in awe. Some people get blasted with criticism the second they publish something and never recover; some people create what they consider their magnum opus and are greeted with a collective yawn; some people learn that they just can’t figure out a way to make a living at this and begrudgingly move onto something else.

Mine came when I read this book:

This week, I was going over changes on the new book with my terrific editor—there is really nothing like having an incredibly smart person who genuinely cares about your book tell you all the things that are wrong with it and how to fix them—when he pointed out a certain crutch I lean on when I get uncertain in my writing. “You get all Eggers arch and ironic,” he said, and considering the book was briefly called Let Us Enjoy This Fleeting Time Together and that there’s a chapter with an FAQ in which the protagonist has a conversation with an imaginary narrative device, I found it difficult to argue with him. And then my editor said something that cut awfully close. “I feel like around 2000 you read that Eggers book when it came out and thought, ‘holy shit this guy wrote this book! I was supposed to write this book!’ and you never quite recovered,” he said. “You don’t need that stuff.”

He was not wrong. Any honest writer has that book, or essay, or reported feature, that they read and realize, “Uh, OK, so I cannot do that. So now what?” Mine came from reading A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius. I read it almost immediately after moving to New York to Try To Make It As A Writer, a particularly precarious time. It wasn’t just that Eggers was young like I was (though six years my senior, I feel obliged to point out), or that he was receiving all the Boy Savant plaudits from serious literary people that I imagined I was supposed to be getting, or even that he was a fellow University of Illinois graduate and therefore I couldn’t claim he had some sort of Ivy League foot-in-the-door advantage that I didn’t. (Far from it.) The problem was that the book was great. Not everything in the memoir has aged perfectly, but the audacity, the intelligence and the raw emotion of it at the time was overpowering; the section in which a faux interview with a “Real World” producer turns, slowly and then immediately, into a naked, tortured howl of grief as he stands over his mother’s coffin remains one of the most jaw-dropping pieces of writing I’ve ever read. We can argue about the turns Eggers’ career has taken—I’m still a fan, but it does feel like he has turned inward in a way that’s the opposite direction from a specific and deeply appealing cultural worldview that he in many ways helped foment, giving his writing less urgency rather than more—but I’ve never forgotten how I felt when I was done reading it: I am not physically capable of writing something this good.

What that book did—and reading the work of others, including friends who were just starting their careers out like I was and were also better than me, people like Jami Attenberg and Choire Sicha and Chuck Klosterman—was make me focus on what I was good at. It snapped me out of the dream land and made me get down to work. What would differentiate me from everyone else? What could I offer that other people couldn’t? I decided my advantage was my willingness—my need—to work. Other people could be more naturally skilled than me. But they would not outwork me.

Stephen King in his book On Writing wrote, “It is impossible to make a competent writer out of a bad writer, and while it is equally impossible to make a great writer out of a good one, it is possible, with lots of hard work, dedication, and timely help, to make a good writer out of a merely competent one.” My goal was to write and write and write and write, so often that people couldn’t help but notice me and what I was doing … and hey, if I caught a break, maybe I’d get a little bit better in the process.

Thus, I got to it. I wrote for free for whoever would have me. I never turned down any assignment, including a glorious six-month stretch in 2003 where I wrote weekly astrology reports for a Website that exclusively covered New York City real estate. (“This is a great week to bring your home to market! Your positive attitude will be rewarded!”) I not only never missed a deadline, I typically turned in pieces several days early. When I ended up running my own blog professionally, I doubled the number of posts that were required of me. I made it my life goal to calm and to please the editors and publishers who paid me to write for them, to make their lives easier so that they would trust me and let me write for them more. I am not sure why I am using the past tense in this paragraph. This are my guiding principles to this date. I write more than is required of me, I say yes to anyone who asks me to write for them, I never miss a deadline. I realized a few years ago—a realization borne out of necessity—that my goal was not to be the greatest writer in the world. It was simply to get to make my living by writing all day, every day, for the rest of my life, until eventually I die, hopefully at my desk in the middle of writing something else. As long as this is happening, I’ll be all right. (Even if I’ve lost the real estate astrology column.)

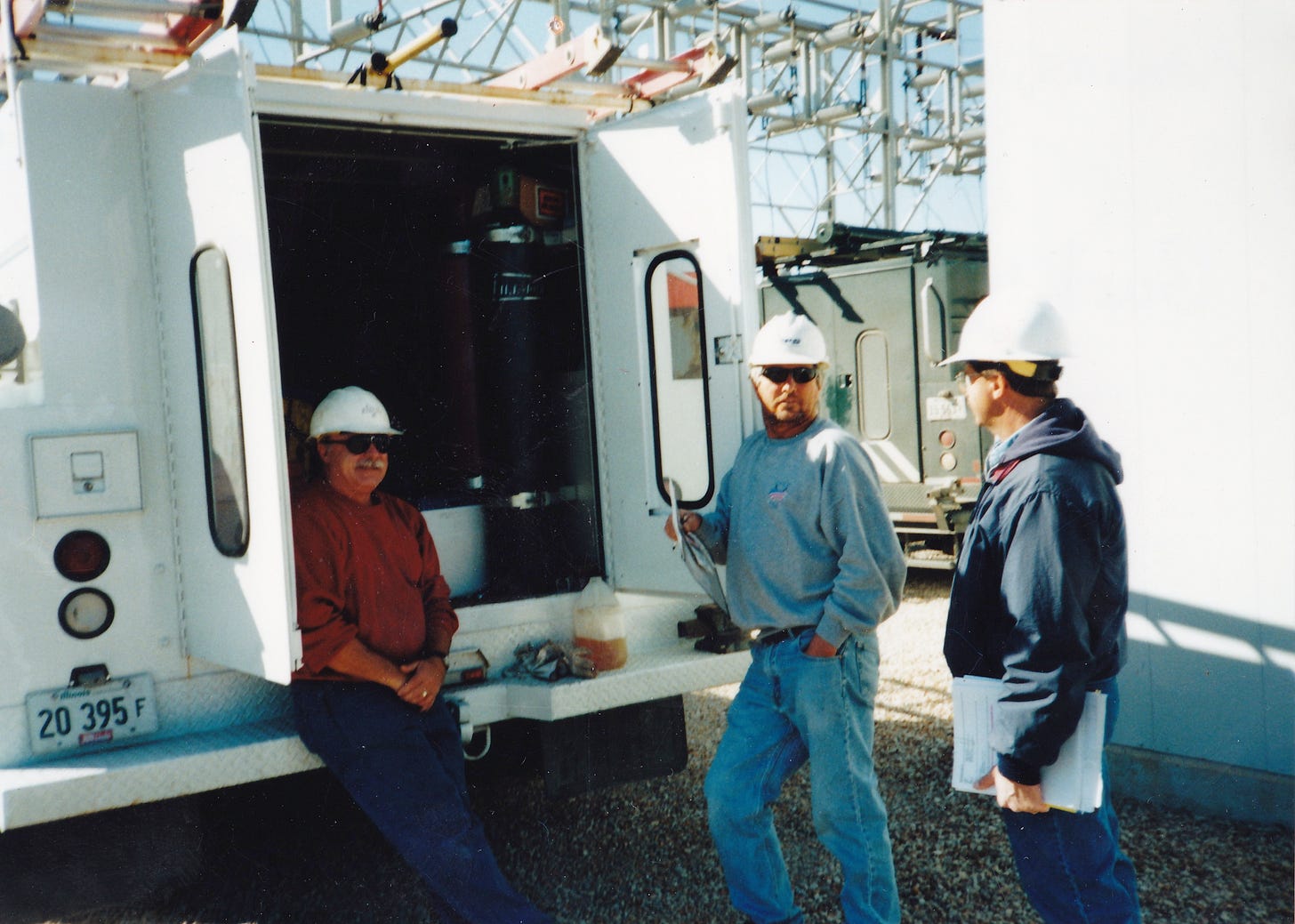

I come by this honestly. The central organizing principle and ethos of the Leitch family has always been work. My father worked as electrical substation troubleshooter for nearly 40 years and never once turned down overtime; we lost multiple Christmas mornings when the dispatcher called him out to a downed power line somewhere. My mother was an emergency room nurse for three decades; my sister spends every day driving hundreds of miles from one sales call to another; my grandfather worked 12 hours a day for the asphalt company he ran; my grandmother wrangled eight freaking children. Whatever you end up doing in your life, whatever field allows you to make a living, you are expected to do it all-encompassingly. Work is a virtue, for its own sake: There is purpose in work, a purity of drive, a North Star to follow regardless of whatever your personal circumstances are at that particular moment. The way out, always, is through work. Work is forever the answer.

This has not made me a great writer, alas. But it has made me a better one, and, more to the point, it has allowed me to keep writing. It has also very much helped me during stressful periods, like, you know, the current one. Writing is not just a place to try to make sense of the madness that constantly surrounds us—it’s a place to escape it. The place I am when I am typing this to you is a different one than the place I’m clumsily tromping around on a daily basis. It’s controlled, and quiet, and it is entirely constructed by me. It gives me order in a world where there otherwise is little. I can obsess over sentence structure and the rhythm of a phrase and capturing a precise tone … so that I do not have to otherwise go spiraling off out of control. I have been fortunate enough to have not faced any deep, destabilizing tragedies in my life, but I know that they are coming, and when they do, I will need work to get me through them. I know that it has been for other members of my family. Work was their comfort. I am sure it will be mine.

I have long espoused this as the only true way to live, the only route I know toward success, or at least sustained sustenance. But as a morsel of macro advice, I have come to see its considerable limits. There is the obvious problem of privilege; it is the habit of those who have reached a certain point in their careers and lives to look backwards and see as work as the only constant, and therefore the only reason, for their bounty when the reality is much, much more complicated than that, and I am certain I am not immune from that. But there is also the question of labor and management and who, exactly, you are producing all this work for. It is one thing to see the drive and purpose of work; it is another for your work to be exploited by those who do not value it in the same way, who see it only as a way to enrich themselves. I have always followed my father’s lead on this, a proud union man who battled with management for decades—to the point that a lockout cost him his income mere weeks before his first child was set to go to college—but never once wavered in his dedication and pride for his job. But telling other people that the only way forward is through work, when that mindset is increasingly used by the wealthy and advantaged to maintain their hold on power, is beginning to feel more like a sucker’s bet. Work is a virtue. I truly believe this. But believing that work will bring you sustained rewards and stability outside the purpose and self-worth the work itself provides … I am not sure this is true anymore. There are many, many questions about America that have become more urgent and glaring in the wake of the pandemic, and this strikes me one of the larger ones. If putting your head down and doing the work like you’re supposed to isn’t going to pay off in the end, where do we go from there? What’s the point of any of it?

These are questions above my pay grade. They matter. For me, though: Work is my only way forward, and always will be. It has always been my only way out. I’m not Dave Eggers, I’m not a phenom pitching prospect, I’m not a unique voice of a generation. I’m just a guy who types, and types some more, and types some more, and will keep doing so as long as you let him. It feels cheating even calling it work, to be honest. The truth is that I’m never more at ease than when I am working, and during a time like this, when being “at ease” is otherwise impossible, its importance cannot be overstated. I was raised to value work above all else, and I am raising my children to believe the same thing. I do not know if this is right. But I do know that it is all I know.

Here is a numerical breakdown of all the things I wrote this week, in order of what I believe to be their quality.

College Football Is Just Rampaging Forward Recklessly, New York. I am not saying that it is driving me a little insane that the local public high school is playing football right now while my third and first graders are staring at a Zoom screen … but it is driving me very insane.

The NL Central Is Still Sorting Itself Out, MLB.com. Little annoying that the Cubs are reaping the benefits here.

X-Men Movies, Ranked and Updated, Vulture. As mentioned last week, I ventured out to an actual movie theater to watch The New Mutants, just for this list. I did this for you!

Big Deadline Deals That Didn’t End Up Mattering, MLB.com. Pointing out that we once made a big deal out of something that, years later, it is made clear didn’t actually mean anything is one of my favorite irritating things to do.

The Thirty: Every Team’s Best Trade Deadline Acquisition, MLB.com. I know the Cardinals didn’t win the World Series with him, but considering the turnaround the franchise made after they traded for him, I feel like the Mark McGwire trade is the most underrated deadline trade in baseball history.

The Thirty: Top Pending Free Agents For Every Team, MLB.com. Doubled up on these this week.

Trade Deadline Predictions From MLB.com Staff, MLB.com. Mine was instantly wrong, of course.

PODCASTS

Grierson & Leitch, “The New Mutants,” “Bill and Ted Face the Music” and “The Personal History of David Copperfield.”

Waitin' Since Last Saturday, we try to figure out whether there will be a season, and what it will look like.

Also, I was on Keith Law’s podcast this week. It was a very fun conversation, much of it centered around this newsletter, all told.

LONG STORY YOU SHOULD READ THIS MORNING … OF THE WEEK

“Going Postal: A Psychoanalytic Reading of Social Media and the Death Drive,” Max Read, Book Forum. This, by my old New York (and sort of Gawker Media) colleague Max Read, is one of the best things I’ve ever read about the Internet. (It also hits at why you haven’t seen me on Twitter, other than to occasionally Tweet out links to things I’ve written, for many months now.) Max calls the urge both to constantly post on and constantly scroll down social media “a Freudian death drive,” and I’m not sure it can be put better.

Also, your requisite Trump story, sorry:

“Trump is Winning the Psychological War on Democracy,” John F. Harris, Politico. Harris remains one of the smartest political journalists alive, and he touches on something here I’ve been thinking a lot about: The actual emotional and psychiatric toll having this person as president is taking on all of us. It’s making us even more insane than we were already, and it’s yet another thing that’s going to take years, if not decades, to fix. It was a very long week, and we have many long weeks left to come.

TWEET FROM MY MOM THAT MIGHT HAVE SOME RELEVANCE TO THE CURRENT MOMENT

ARBITRARY THINGS RANKED, WITHOUT COMMENT, FOR NO PARTICULAR REASON

NFL Teams, Ranked by Appeal of Being Played As in Madden 21

Kansas City

Baltimore

Arizona

Tampa Bay

Green Bay

LA Rams

New Orleans

Cleveland

Buffalo

San Francisco

Seattle

Tennessee

Houston

Minnesota

Philadelphia

Atlanta

Las Vegas

Dallas

Cincinnati

Indianapolis

New England

Carolina

Chicago

Pittsburgh

Miami

Denver

Detroit

NY Jets

LA Chargers

Washington

NY Giants

Jacksonville

ONGOING LETTER-WRITING PROJECT!

If you are one of those people who forgets to check their mail, this is a good week to remember. I got a lot of these out this week.

Will Leitch

P.O. Box 48

Athens GA 30603

CURRENTLY LISTENING TO

“How Lucky,” John Prine. Hey, the book has a new title. This is it.

Remember to listen to The Official Will Leitch Newsletter Spotify Playlist, featuring every song ever mentioned in this section.

Cases are currently spiking here in Clarke County, the highest they have been the entire pandemic, largely because the students are back.

So that’s nice. Masks up, people.

Have a great weekend, all.

Best,

Will