Here is a button where you can subscribe to this newsletter now, if you have not previously done so. I do hope that you enjoy it.

This fall, for the last time, I am coaching Little League Baseball. I had coached Little League every spring since my son William, now almost 11, was five years old and in T-Ball, before retiring a year ago. It was time. I love coaching little kids, but if I had my druthers, we wouldn’t even keep score at Little League Games; it would just be learning the rules and falling in love with the game and goofing around and calling each other funny nicknames and occasionally somebody accidentally whacking their coach in the head with a bat. All that works in T-ball, but as kids get older, parents and other coaches start getting more invested in the scoreboard (as I’ve written before, scoreboards are bad, scoreboards make everything worse, scoreboards are why everyone is always so unhappy all the time), which changes everybody’s priorities including, if one isn’t careful, one’s own. So I retired. It was infinitely more relaxing just to go watch my kids’ games from the stands, to volunteer in the concession booth, to cheer everybody on but not have any sort of investment in any particular game’s outcome. Let them people who care about that care about that.

But I came out of retirement this fall, for one last season, for one reason: Because of the age rules of fall ball, it would be the only time I’d ever be able to coach both of my kids on the same team—to “get your Cal Ripken Sr. on,” as a friend put it. To be able to have both my sons on the same team—my extremely different, two-and-a-half-years-apart sons, both of whom are getting older and learning their own personalities and constructing lives that involve their parents a little less every day—was an opportunity I could not turn down. Who knows how many more chances I’ll have to spend this much sustained time with them? Every minute, they move a little bit farther along that necessary, but painful, transition into a world where their friends are the center of the universe, rather than their parents. I want to hang onto every second with them while I can.

So I signed up for coaching, a fall ball team of 11-12-year-olds, along with the eight-year-old Wynn and his nine-year-old best friend who has turned out to be a tough little catcher. I will confess that there are sometimes some size disparities in the league.

(And William is one of the biggest kids on my team!)

But we are having fun, even as the scoreboard keeps getting in the way. (We’re 0-7, though most of the games have been close, which of course just makes it worse.) But what’s more interesting to me is to see how off the field is reflecting what happens on the field. You can see how all these kids have been through—who have all been raised in our current American culture, through Covid-19 and virtual schooling and Trump and technology and all of it—reveals itself in how they react during moments of on-field stress. I think you can learn a lot about what we’ve put our kids through by Little League—specifically, how they play Little League right now, in 2022.

I have long thought that our (and especially the previous) generation has put an unfair, but necessary, burden on our children to basically have to fix everything we have broken. Some of the things I’ve noticed in Little League this year are good examples of how much work they have to do. This is what we’ve done to them.

Here are some takeaways from a month of Little League coaching, as a father, as a baseball fan, as a human being alive in this historical moment:

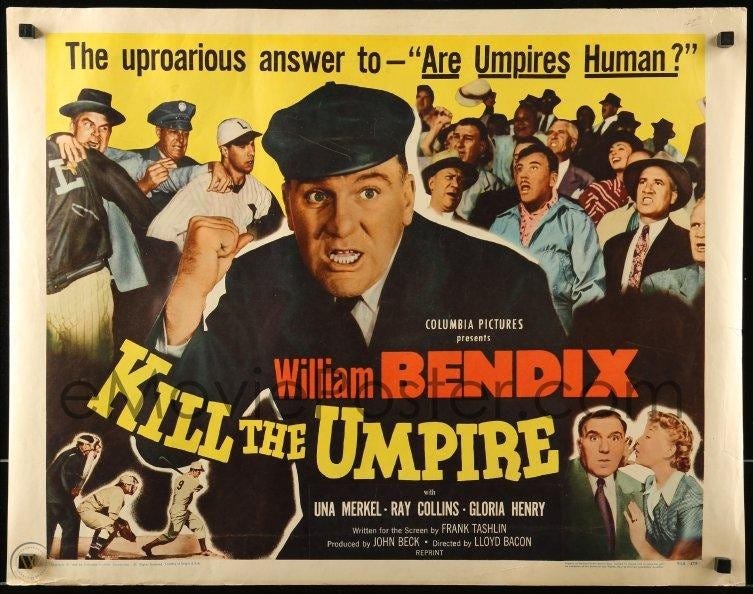

Because of K-Zone and StatCast and instant replay, children believe umpires are irreparably stupid and their sworn enemies. My late grandfather, Dennis Dooley, was the most famous Connie Mack League youth baseball umpire Moweaqua, Illinois, had ever seen. An retired military man with a buzz cut, six-pack abs and his dog tags hanging around his neck, he exuded authority and omnipotence. For 25 years, every kid in Moweaqua knew Mr. Dooley, and they knew he was not to be questioned. Once, a kid slid into home plate, and Grandpa called him out. The kid jumped up and yelled, “I was safe!” Grandpa stood over him, his dog tags dangling in the kid’s face. “No,” he said, calmly but firmly. “You were out, because I said you were out. You’re out, by definition. I am the law here.”

This is how we once looked at umpires, in an age of law, of authority, of firm adherence to rules and tradition. They were an institution—the institution. The umpire said you were out, so, thus, by definition, you were. But this is not how kids see umpires now. An umpire is no longer an arbiter of truth; an umpire is a simply a human being, prone to the same foibles as the rest of us, and always, always more wrong than a computer. Kids have been raised to see an electronic box that tells them—to their minds, definitively—when a pitch is a strike and when it is a ball, and more to the point, when the umpire has made a mistake and is therefore not to be trusted. And, I have to say, they now have zero respect for umpires.

Every call that goes against them—every single one—is cause for their eyes to pop out of their head in disbelief. And they believe (incorrectly, I’d argue) that there is a singular truth out there, if only there were some way to prove it. One of my favorite moments of the season was when there was a bang-bang play at first base, and the runner was called out. Upset by the call, the player cupped a hand to each ear, which, in the major leagues, is a signal to call for an instant replay from the review facility in New York.

You felt almost bad informing him that, uh, no, this Little League field with a pothole at third base and a puddle in front of home plate, staffed by volunteers and teenage umpires making five bucks a game does not, in fact, have a centralized technology center that can review every play on the field.

But that is what kids think now: That if a call goes against them, it’s inherently wrong, and someone, somewhere else, somehow, can correct this injustice. Fans spent decades yelling “Kill the umpire!” at baseball games. I’m pretty sure we’ve now actually done it.

The default state is aggrievement. Personal responsibility is a fool’s errand. We’ve lost all seven games we’ve played—mostly because we have a terrible, stupid coach who does everything wrong—so we’re certainly prone to this, but you see it with every team. If something hasn’t gone the way a kid wants it to, it is not because of a mistake that they made that they can now learn from to aid them in the future: It’s because of something someone else did. The umpire is an idiot. The other team is cheating. That kid is too old and shouldn’t be in this league. The coach should have played me at a different position. It’s too cold out tonight; it’s too hot out; the weather is too perfect and is thus distracting.

I know that “personal responsibility” has become a loaded buzzword that the disingenuous have used to excuse their lack of desire to help people who need help, to fulfill their responsibility to their fellow citizens and fellow humans. But in sports, the only way to get better is to figure out what you’re doing wrong and work the best you can to correct it. I am not sure we are training our kids to do this, mostly because so many adults are so loathe to do it themselves. The perpetual state of default aggrievement is the single biggest change I’ve noticed in American life over the last 10 years—the reflex to blame someone else for everything, to see everything that hasn’t gone perfect in one’s own life as the fault of an ideologically convenient “other”—and it is not surprising that our children have internalized it.

Inherent tribalism. For one game, I thought we were going to be short a couple of players for the game, so we drafted a player from another league to fill in for us. I introduced him to the team, and they welcomed him, and then, when the game was about to start, it turned out we had enough players but the other team didn’t, so we sent him over to the other dugout. This actually made a couple of kids on my team legitimately angry, thinking that he—a super sweet kid they had literally just met—was a “traitor.” This transfers over seasons too. There are players who were teammates in the spring but are now on opposite teams are thus now sworn enemies. The Us. vs. Them mentality is ingrained, even amongst friends. Wearing a different jersey—on the field, in politics, in life—instantly makes you an enemy to be vanquished.

Everything is so emotional. We were at a third-grade parent-teacher conference this week, and the (excellent) teacher was telling us how she’s had to teach basic things, like how to hold a pencil when writing, and how to work alongside someone you might not necessarily get along with, that she’s never had to teach before. “It’s because of those lost years at the beginning of the pandemic,” she said. “They all just missed a lot.” I notice this most when kids are dealing with failure. They get so upset. They’re so hard on themselves, so frustrated that they couldn’t do something that they desperately wanted to, so crushed by self-imposed pressure, that they crumble incredibly quickly. Everything is just very fraught. I try to keep in mind, with adults, that we have all been through a lot in the last two-plus years, and that no one is really at their best, still. But it has been even harder on children. And I think you can really see the seams showing … how hard they’re working to keep it together.

The kids are all right. And yet they just keep going. One of the most thrilling things about being around these kids is how, through it all, truly tough they are. They have gone through a period of history that is as stressful and difficult and potentially damaging as any of the last 50 years, and they keep fighting through it. They struggle, they grouse, they cry, they grasp for explanations, they fall … but they keep on coming. There is a strength in them that is undeniable. And you can tell because, well, because they’re so good. I’ve seen a lot of kids in this league and others, and I haven’t seen any bullies, or jerks, or cocksure brutes who push other kids around or who act like they’re better than anyone else.

And they are supportive of each other. It’s as if they can sense how hard it is for other kids, and do what they can to lift them up. When they see weakness, they want to tend to it, rather than exploit it. They want to help each other.

They’re all a little unsure of themselves, a little cautious, a lot scared … but they keep going out there and doing their best, in spite of it. One of the hardest things as an adult is seeing people who have, in one way or another, given up, or, at the very least, decided that they simply do not value themselves, or strive, in the way that they once did. They have stopped believing. But not a single kid, on my team or any other, has ever once stopped trying, or thrown their hands up in total despair. They are going to be facing a world that is going to be almost unfathomably difficult for them. They’re going to need every bit of resilience they can muster. They’re going to have to be tough, but more, they’re going to have to be good-hearted: They’re gonna have to be kind. And I see it. I see it in every single one of them. And it makes me want to make sure to be kind too.

This is my last year of coaching baseball, and, again, it’s probably for the best. As they get older, my utility is diminished. They don’t need a cheerleader and a morale booster when they’re a teenager: They need someone who will tell them how to hit the cutoff man. This is it for me. But I will miss it. You learn a lot about humanity when you spend a lot of time with kids. Not all of it speaks well to us. But it speaks well to them. I think they’re gonna save us. I think they’re gonna have to.

Here is a numerical breakdown of all the things I wrote this week, in order of what I believe to be their quality.

The NFL Isn’t Going to Do Anything About Concussions, New York. We know this by now, right?

A Smart Wild-Card Series Strategy Teams Should Use, But Won’t, MLB.com. Do it and be legends, you cowards.

The Fifty Best Players in the Postseason, MLB.com. This is a fun annual piece to do, and always gets me yelled at.

Cate Blanchett Movies, Ranked and Updated, Vulture. Updated with TAR.

Do Not Assume Herschel Walker Is Going to Lose, Medium. Sad to say.

Velma Being a Lesbian Is Actually Scary to a Lot of People, Medium. Some people just want to be scared.

I Made MLB Playoff Predictions That Are All Obviously Going to Be Wrong, MLB.com. That’s the Leitch Guarantee.

Your Friday Wild-Card Previews, MLB.com. Already outdated!

Your Saturday Wild-Card Previews, MLB.com. Not outdated yet!

PODCASTS

Grierson & Leitch, no show this week because of travel.

Seeing Red, Bernie and I previewed the playoffs. (And recapped Game One this morning, though it was difficult to do through all the blood.)

Waitin' Since Last Saturday, we previewed the Georgia-Auburn game and recapped the Georgia-Missouri game.

LONG STORY YOU SHOULD READ THIS MORNING … OF THE WEEK

“Letters to Jeb Bush,” Adam Dalva, The New Yorker. Starts out as something, then takes a great turn and becomes something else. Jeb Bush seems like a really nice guy!

ONGOING LETTER-WRITING PROJECT!

This is your reminder that if you write me a letter and put it in the mail, I will respond to it with a letter of my own, and send that letter right to you! It really happens! Hundreds of satisfied customers!

Write me at:

Will Leitch

P.O. Box 48

Athens GA 30603

CURRENTLY LISTENING TO

“Bittersweet Me,” R.E.M. We haven’t had an R.E.M. song in a while, time to rectify that. I still think this might be the most underrated R.E.M. album.

Remember to listen to The Official Will Leitch Newsletter Spotify Playlist, featuring every song ever mentioned in this section.

I don’t even remember liking baseball. Have a great weekend, all.

Best,

Will

Interesting observations on children. Thanks for the hopeful conclusion. And the Long Read suggestion was excellent as usual!

Many thanks!