Here is a button where you can subscribe to this newsletter now, if you have not previously done so. I do hope that you enjoy it.

This week, on the Hacks On Tap podcast, former Obama advisors David Axelrod and Robert Gibbs (and my old Culture Caucus co-host John Heilemann as guest) tried to have a legitimate, good-faith discussion to figure out how it came to be that 70 million people would vote for Donald Trump, and how one of the two major political parties in this country would go so far down the rabbit hole that it would actively support the overturning of American democracy by inventing false, fantastical narratives of widespread voter fraud in order to keep their leader in power despite his clear electoral defeat. Axelrod, as intelligent and thoughtful a figure in the political space as you will find (even if he is a Cubs fan), had a theory as to how this has happened: The condescension of elites, primarily those in his own party.

“Elites tend to speak from that position of moral imperative,” Axelrod said, after discussing the early days of the pandemic, when small non-essential businesses were asked to close in order to stop the spread of the virus. “People think that these smarty pants elites on the coasts and in the Democratic party just don’t give a shit about them. I live in rural Michigan, and by and large, I don’t feel like my neighbors are talked to very much. And they feel like they’re being talked down to, constantly. Even if you’re just trying to get them to do what is right. So they turn to someone one like Trump. Who doesn’t talk down to them. Even if he doesn’t give a shit about them.”

This is a very empathetic and forgiving way to look at our current predicament. I am doing by best to understand and grapple with it. It is not always easy.

About eight years ago, I was having dinner back in my hometown of Mattoon, Illinois, with my parents, my sister and a few members of our extended family. We were talking about my uncle Mike and his longtime companion Dave (known merely as Uncle Dave, discussed in more detail here and here), and how, after nearly three decades together out in Philadelphia, they were talking about getting married, now that it looked like they might legally be able to. Mike and Dave had spent essentially every second together for 30 years and were more compatible and inseparable than any other couple any of us had ever met, something we all vividly knew, having spent the last 30 years together with them ourselves. But upon hearing this talk of marriage, one of my relatives spoke up.

“I’m sorry, but … that just doesn’t seem right to me,” she said. “Does that just seem wrong to everybody else? Two men getting married? I don’t think that’s right.”

Everyone at the table went silent. She was not a particularly religious person; this was not coming from a “The Bible says it’s a sin” angle. The idea just made her personally uncomfortable and thus didn’t think these two men, who, again, we all loved deeply and knew to be as close to a perfect couple as you could possibly imagine, should be allowed to be married. We were all stunned, but, of course, it was me who spoke up, because, well, I found it, as Axelrod might have put it, to be a moral imperative.

“How can you say that?” I said. “You know Mike and Dave are as ‘together’ as you and your husband are, or my parents are. Why shouldn’t they be able to get married? How can anyone justify that?”

She sort of grinned a little, quietly, as if she were in on a joke that I wasn’t. “Well, Will, of course you would think that,” she said. “You’re a liberal elitist.”

To hear this from a woman who had grown up in the same town as I had, who had been at my high school graduation, who had known me so long she had given me baths as a baby, who had seen me sport a variety of mullets and rattails, who had fixed me and my cousin fried bologna after we’d spent all day out in the woods throwing rocks at raccoons … I couldn’t comprehend it. My upbringing was exactly the same as hers. I was as “elite” as she was. We are members of the same family.

“You must have learned all that at college,” she said, and then my mom was smart enough to change the subject. We all got back to our chimichangas and the Illini. Dave died before Pennsylvania made gay marriage legal, so they never did quite make it. Later my mom, who loved her brother and very much wanted him to get married, chastised me for speaking up. “You’re never going to convince her,” she said. “All saying that did was make you feel better. And ruin dinner.”

******************

Of all the divides in this country, the deepest, particularly among white people, remains the divide between those who have had a college education and who haven’t. I understand this divide, though not because I particularly remember learning all that much or getting all particularly smarter in college. I do, however, remember meeting people who had different experiences than the ones that I had growing up, and being intrigued enough by these people and their experiences that I wanted to meet more of them. That led me to living in other cities, and meeting even more different kinds of people, in Los Angeles, in St. Louis, in New York, in Athens, Georgia, all of which challenged everything I thought already knew about the world. This seems to be the point of living: To be a little smarter, a little better, tomorrow than I was yesterday. That’s what I got out of college. That was why it was so worth it to go.

And it was a big deal to go to college in the Leitch household. I was the first kid from my family to go to college, something I didn’t appreciate as a big deal as the time but now am a little overwhelmed by the magnitude of. My father was of the generation that did not go to college but saw being able to send his children there as a tangible representation of success: A large part of the American promise, until fairly recently, was that, through hard work and dedication and prudent decision-making, your kids could have a better life than you had. You were always supposed to pay that forward. My dad worked to the bone to take care of his family and send me (and my mom and, later, my sister) to college, and while college had always felt like the obvious thing I would do after I graduated from high school, to him it was a massive life achievement and thus a point of considerable personal pride. Every year that goes by, I feel more grateful to have a father who saw education as such a priority. (And more guilty about all those classes I skipped and all those C’s I scraped by with.)

I had friends, family members, who would call me “College Boy” when I’d come back to Mattoon over Christmas and summer breaks, and it was always good-natured, even said with a little bit of pride themselves. My cousin would always congratulate me on “getting out” of Mattoon, but I never felt that way: I loved my hometown, and missed it. (I still do.) After all, college had made me feel like an outsider: I always felt like a Mattoon kid around fancy Chicago suburban people, in a not dissimilar way than I felt like a Mattoon kid in Los Angeles, in New York, even here in Athens today. I didn’t feel more educated, or smarter. I was just in a different place. Which was, to many, achievement enough.

But then again: I never could shut up. I did feel that some of the beliefs of the people I grew up with were ignorant and closed-off, were reactionary and dismissive of the outside world. Not all of them. Not even a majority of them. But some of them. And I felt, again, that moral imperative to push back. It was wrong to be against gay marriage. It was wrong to think Barack Obama was born in Kenya. It was wrong not to see widespread systematic racism, or deep-seated inequality. I had to say something. Right? It could only help. Right?

I never felt all that different, at my core, than the kid who grew up in Mattoon. To me, I hadn’t changed much. I might not have been right, though. The trips home felt a little bit more different every time. And when I go home now, I barely even recognize the place. I wonder if it recognizes me.

And, meanwhile, today. There are record COVID cases there every single day right now. On Friday, there were 102 COVID cases in Coles County, Illinois, a county that only has 50,000 people in it. That is one out of every 500 people in Coles County who tested positive for COVID on Friday. There were 81 COVID cases in Clarke County, where I live, on Friday. Clarke County has three times as many people in it as Coles County does, and those 81 cases one so alarmed Clarke County that it shut down the public schools this week.

It all becomes rather stark.

******************

The pandemic has shed light on so many problems that we knew we had but thought we could get away with. One of the primary ones is how we share our collective space—how truly We Are All In This Together we really are. And if we differ with our neighbor on what the “correct” way to navigate this once-every-100-years event, what that means for our co-existence moving forward.

I can know the facts, or at least think I do, about staying safe in this pandemic, but if I run into someone who has decided not to wear a mask, who has justified their lack of caution with vague, thoughtless notions of “herd immunity,” who has convinced themselves this is all some big overreaction, I cannot persuade them otherwise. It is incomprehensible to me that someone could look around and see 3,000 people dying every day, our schools closed, sporting events with no fans in the stands, restaurants and movie theaters going out of business, every aspect of human life on this planet upended in every possible way, and think, “everyone is making too big of a deal out of this and this won’t affect me or anyone in my life.” But this is exactly what’s happening, still. This is happening among some of my friends and family. It may be happening in yours.

Then again, there are people who might look at some of my decisions and think that I am being unnecessarily risky as well. I don’t have all the answers, not even close. We are all, in a way, fumbling around in the dark here, and a true accounting of the wisdom or our decisions during this time likely won’t be available until years from now, when it’s all long over, when we can all see a little more clearly.

Those questions—what do you say? What can you say? What moral imperative do you carry? When does speaking up just become lecturing and chastising, and thus just make everything worse?—are the driving force of right now, what we are forced to reckon with and wrestle with just to get through every day. I’ve got friends and family, people I care about, people I respect, who are constantly eating indoors, unmasked, or are hosting dinner parties for friends regularly, still, in the middle of this surge. I could tell them what they are doing is wrong. I believe it is not only wrong, it is actively hurting the rest of us: It’s leading to more hospitalizations and deaths, it’s keeping my kids out of school, it’s making this last longer and be exponentially more painful.

But what good would that do? Does it actually help? Or am I just planting more seeds of discord, making the chasm between us only wider and more difficult to bridge once this is over. I mean believe that collective action is the only thing, until the vaccine is deployed, that can save us, but I am kidding myself to think that collective action is possible right now. So who I am talking to? What change am I trying to affect? Am I just doing this to make myself feel better? And maybe it’s worth ruining dinner for anyway?

I do not know the answer to these questions; they did not teach that class in college.

I know that this whole newsletter has a been a little scattered and unfocused. It’s a scattered and unfocused time. But it’s all coming to a head now. The vaccines are here, we’re going through a nightmare period but we’ll be out of it sooner than we could have imaged, people are trying to overturn an election and talking about secession, the kids can’t go to school, 2020 is ending in a fevered rush, culminating in absolute madness. We’re all about to be in a different place in a few months. But will we have changed at all? What have we said that cannot be unsaid? How do we all live together after this?

I never have the answers to any of these questions. Maybe I should stop asking. Perhaps the only logical answer is stepping outside, appreciating what you have, holding onto those you care most deeply about and hoping like hell for the best, for them and for the rest of us. We can’t fix everything. We can’t even fix ourselves. But we can get to the next moment, and then the next one, and then the next one. Every year, that feels more and more like a victory. Like that’s the point of the whole damn thing.

Here is a numerical breakdown of all the things I wrote this week, in order of what I believe to be their quality.

Reasons to Love New York: Foley’s NY, New York. This probably isn’t the best piece I wrote this week—it’s certainly the shortest—but I was so delighted to be back in the annual Reasons To Love NYC issue this week that it goes straight to the top. I was in this every year from 2007-14, and then haven’t been since, what with the whole moving-away-from-New-York-City thing. It is my favorite issue of any magazine every year, and it’s particularly great, and sad, this year.

The Amusing History Between Lance Lynn and Tony La Russa, MLB.com. I’m one of the few TLR defenders you will find, but even I am concerned with how long he’s been gone from the game. He was considered too old 10 years ago!

There’s Disinfo in the Car Pool, Medium. Well, there is. A lot of it.

How Sports Are Adjusting While Waiting For a Vaccine World, New York. I am fairly certain this constant writing about vaccines is a coping mechanism.

Can Warnock and Ossoff Really Win in Georgia? Medium. I will confess I am not sure.

MLB Year in Review: Five Teams Who Enjoyed 2020, and Five Who Didn’t, MLB.com. A new weekly feature until the end of the year.

Revisiting the Top 10 Free Agent Signings of Last Year, MLB.com. Madison Bumgarner went from World Series Hero to Contract Albatross shockingly fast.

Five More People Helping Us Through the Pandemic, Medium. Honestly, they should just rename December “Recapping The Previous Eleven Months.”

The Thirty: Bounceback Candidates For 2021, MLB.com. Time to maybe be honest about Jack Flaherty?

PODCASTS

Grierson & Leitch, we discuss the great Nomadland, along with Mank and Small Axe: Red, White and Blue.

People Still Read Books, talking with Tara Ariano and Sarah D. Bunting, authors of A Very Special 90210 Book.”

Waitin' Since Last Saturday, previewing the Missouri game.

LONG STORY YOU SHOULD READ THIS MORNING … OF THE WEEK

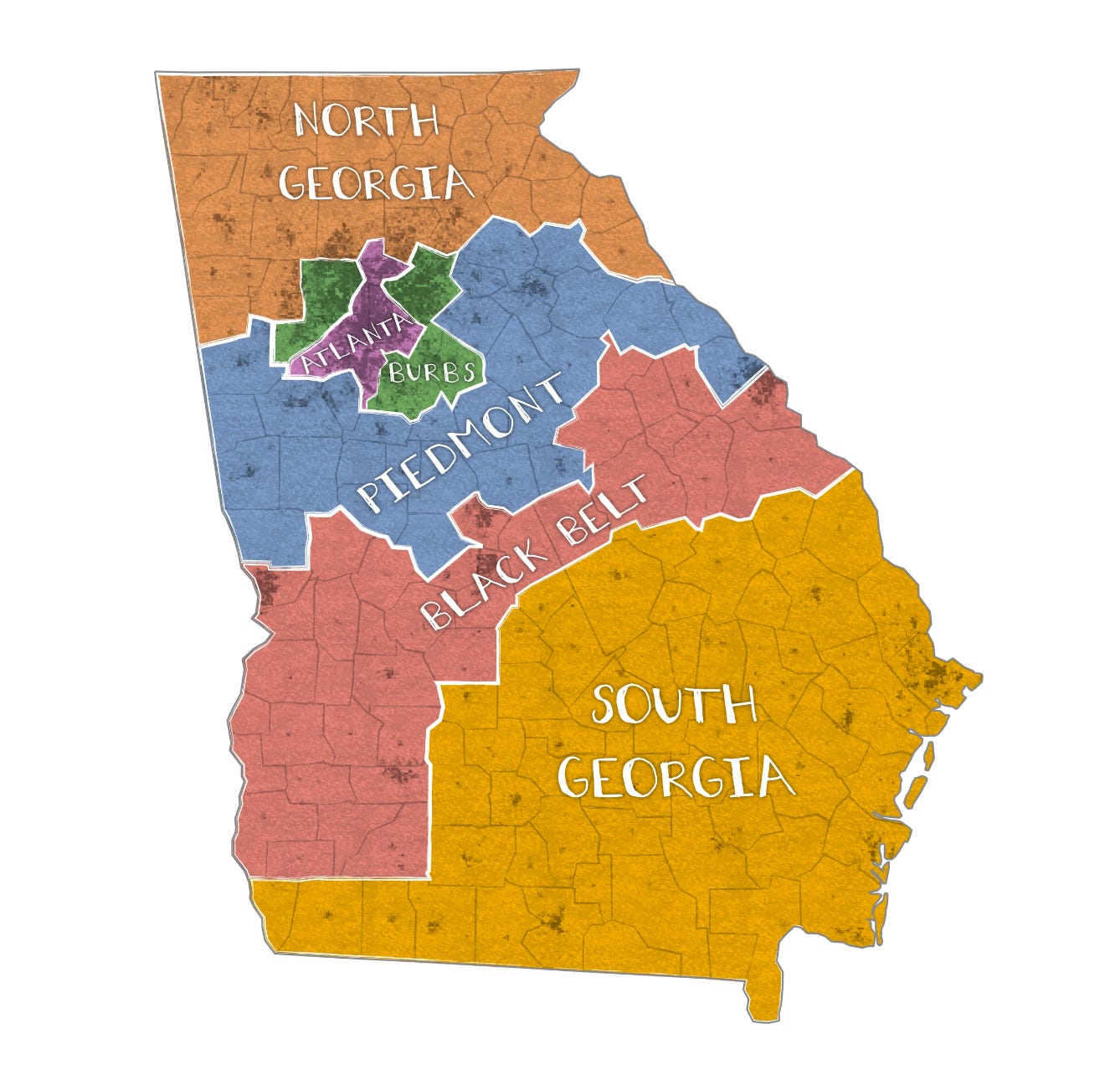

“The Political States of Georgia,” Dave Weigel, The Washington Post. Dave Weigel might be the best pure political reporter alive, and his The Trailer newsletter is essential. This breakdown of what the state of Georgia looks like, both in the last election and the upcoming runoff Senate races, tells you everything you need to know.

Also, this Jamelle Bouie piece in yesterday’s New York Times lays it all right out there.

ARBITRARY THINGS RANKED, WITHOUT COMMENT, FOR NO PARTICULAR REASON

Books I Am Proud of Writing in My Life, As Ranked By How They Have Aged and Hold Up in the Year 2020

ONGOING LETTER-WRITING PROJECT!

Whew, I’m finally caught up on these. So send me more! Write me at:

Will Leitch

P.O. Box 48

Athens GA 30603

CURRENTLY LISTENING TO

“Do Me A Favour,” Arctic Monkeys. The Arctic Monkeys are one of the most truly listenable bands in my little universe: I always write a little bit faster and harder when they’re playing. I even like that weird little concept album they did last year. They have a scorching live album, “Live at Royal Albert Hall,” that just came out last week. This song is a particular highlight.

We had a cool guy you should vote for visit us in Athens yesterday.

(Terrific photos from The Red and Black’s Taylor McKenzie Gerlach, even if my head didn’t get out of the way of one of them.)

Best,

Will