Volume 4, Issue 12: Tommy Edman

"To go out there and play every day, whatever position you need him, provides a real value to this team."

Here is a button where you can subscribe to this newsletter now, if you have not previously done so. I do hope that you enjoy it.

The new book is due in exactly one month. It’s another novel—I’m contracted for two more of those now, counting this one—and I’m close. I am excited about how the book is coming together, and while I haven’t entirely figured out the ending yet, that’s close too. I do not know if people will like the book, or if it will get great reviews, or if it will sell a million copies. I cannot control any of that.

But I do know one thing: I’m going to turn it in on time.

This is my thing. I’ll never forget the reaction of David Hirshey, my old editor and lifelong friend, when I send him my initial manuscript of God Save the Fan way back in 2007. After staying up all night to polish it up, I called him and said, breathlessly, “I finished it! I did it! I hit the deadline.” He burst into laughter.

“Wait … you thought your deadline was real?” he said. “I didn’t even know your deadline was today. That’s hilarious. What kind of writer are you, turning things in on time?” David told me, in all his years in publishing, only two people had turned in their books on time. One was me. The other: “John Daly. And I’m sure he hadn’t even read it.”

When I first moved to New York City to try to become Mister Great American Writer Person, it became very clear to me, very quickly, that just about everybody I met was more talented than I was. They had better training, or better schooling, they’d lived more interesting lives than I had, they were just smarter and wittier than I was: sometimes I’d just get lost listening to them talk. I was, pretty clearly, in over my head. A reasonable person would have called it right then and there and moved back to the Midwest to go write ad copy, buy a house in the suburbs and live a perfectly comfortable, sane, pleasant life. But I had convinced myself I was all-in at that point. After all, I was 24 years old: I was running out of time.

So I tried to think about what would make me stand out—what I could provide that no one else could. The one thing I noticed that all those up-and-coming writers had over me was that, well, they were a little lazy. They wrote only when they felt like it, when they were inspired, and they were always complaining about how editors didn’t understand them, how editors were always trying to change their perfect, brilliant prose, how writing was such an eternal struggle. I didn’t feel this way about writing at all. I loved writing, found it the only place I could make sense of the world, the one calm spot amidst unceasing chaos. (I still do.) And I knew I could be productive. I wasn’t precious about my writing, didn’t think it was anything special, or at least not special to anyone other than me. But I did know I could write a lot. I knew I could make stuff. I knew I could make a lot of it.

I wasn’t going to be better than any of those people I met. But I did think I could probably outwork them. So that became my strategy, and my primary focus: Work harder. Say yes to every assignment. Write all the time even if no one was paying me, or even if no one was reading it. Be ready for opportunities and be willing to try new things, even if I would probably be bad at them.

And more than anything: Turn in everything on time. Always. I had friends who were editors, and most of my conversations with them were about how frustrated they were with their writers, how they were late on a story, how they would inevitably turn in something half-assed that the editor would have to spend hours cleaning up or even just rewriting entirely. “Why do you keep working with them?” I’d ask them. They’d shrug. “They’re writers,” they’d say. “It’s just how they are.” I tried to imagine how much electrician father or my nurse mother, people who worked 12-hour shifts, on their feet all day and night, for 40 years, would feel if they learned their son was turning in all his work late and expecting other people to fix it for them. I decided that wouldn’t be me. I might never be a genius. But I could definitely turn in my shit on time.

And that was what opened everything up. Being the writer editors could rely upon, the one they knew would file clean copy on deadline, or even before deadline, got me more assignments, and more, and more. Editors have stressful, exhausting, highly disorganized lives. Filing everything on time scratched one task off their to-do lists, took some weight off their shoulders. Which made them want to work with me even more. Eventually, this led to Deadspin—which, more than anything else, was reliant on being constantly productive and not particularly sensitive about your precious words—and then to New York and the Times and MLB.com and Bloomberg and everywhere else I get to peddle my wares. Not because I am particularly talented: Because I make editors’ lives easier. You can get away with a lot of stuff if you work to make other people’s lives easier. When editors trust you, you are given an enormous amount of leeway. On the day Donald Trump announced his candidacy for President in 2015, I was allowed to write a 2,000 word piece about Trump and American celebrity and the ubiquity of branding (particularly in small towns and parts of the country where the name Trump itself represented the higher of American wealth and prosperity) that began with an extended anecdote about my late grandmother in Moweaqua, Illinois. The piece led the Bloomberg website for two days and was featured on the “CBS Evening News;” it got Scott Pelley to say my grandmother’s name on national television, a decade after her death. The only way you’re allowed that much freedom is if your editor trusts you. And you only get that freedom by turning things in on time.

Last weekend in Champaign, I spoke with a bunch of journalism students, all of whom, just like we were back in the day, were terrified that they’ll never get a job, that their careers will never get going, that their parents will forever be disappointed in them. They wanted to know what we wanted to know back then: How do I make it? The answer is infinitely complicated, of course. It’s a mixture of kismet and luck and timing and persistence and inherent privilege and irrational belief and the whole stew of randomness that makes up a human life. But the one thing you can control—not your talent, not your circumstances, not whatever indifferent corporation you end up working for that will drop you in a second and not so much as blink about it—is what you do. You can do the work. Maybe it will turn out well for you, and maybe it won’t. Maybe you’ll catch a break, maybe that break never comes. Maybe you’ve dedicated your life to a series of corporate masters that only see as a cog in their machine; maybe you’ll land in the exact right place and change the world; maybe you’ll finally get tired of the struggle and quit to go write ad copy in the Midwest and finally have a happy life. So much of that, so much of everything, is out of your control. The only thing you can control is your own productivity—your own dedication. Again: That still may not work, and you might learn someday that it’s not even worth it to you if it does. There is always a cost to everything, even hard work. But if you want to succeed, however you define “success”: If you’re not born with a yacht already named after you, I honestly don’t know any other way.

I know this answer is unsatisfying, because there are so many people, deserving people, who work hard and don’t make it, whatever “making it” is. I am not claiming hard work and diligent attention to detail—often at the expense of a balanced, healthy life—is a magic bullet, because it isn’t. It’s even toxic to claim anything close to that, because it implies that the reason people don’t get the things they want is because they didn’t work hard enough, which isn’t true in about 40 million different ways. But I do think the work has to be put in, at a base level, just to be in the game, if even just so, if it doesn’t work out, you can look yourself in the mirror and say, “I did all I could do.” Or you realize that this turns out not to be what you wanted in the first place.

I will turn this book in next month, and then they’ll give me another deadline for the next one, and I’ll hit that one too. Hopefully those will do well enough that they’ll let me write some more after that, because I very much enjoy making them. I cannot control that: Maybe the books will sell enough, and maybe they won’t. But when they make the decision whether or not to let me write another one, the one thing I don’t want them thinking is, “oh, and he’s a huge pain in the ass to deal with, always late on everything.” After all: They should get to enjoy their jobs too. I will turn this book in on time. I will turn it all in on time. I do not think this makes me special. It’s precisely because I’m not special that I feel required to do it. I’m not sure there is any other option. At least until I hire John Daly’s ghostwriter.

Here is a numerical breakdown of all the things I wrote this week, in order of what I believe to be their quality.

The Ten Oldest Players in Baseball, MLB.com. One of my favorite pieces to write every year. You are so old.

How Much Are the Bills Worth to Buffalo, Really?, New York. A qualitative analysis rather than a quantitative one.

Life As a Non-Covid Getter, Medium. So far, anyway.

From the Archives: We’ve Forgotten How To Fear, Medium. One of the best things I’ve ever written, seemed like a good week to bust this one out.

The Thirty: One First Impression For Every Team, MLB.com. I have watched me a lot of baseball so far.

Your Friday Five, Medium. Would you like us to assign someone to butter your muffin?

PODCASTS

The Long Game With LZ and Leitch, we talked to New York State Senator Sean Ryan about the Bills, as well as previewed the NBA playoffs and talked about MLB streaming services.

Grierson & Leitch, no show this week, back next week.

Seeing Red, Bernie and I looked at the first week of the season.

Waitin' Since Last Saturday, we previewed G-Day, which is today. (I will not be there.)

LONG STORY YOU SHOULD READ THIS MORNING … OF THE WEEK

“Why the Past 10 Years of American Life Have Been Uniquely Stupid,” Jonathan Haidt, The Atlantic. Oh, so that’s why.

ONGOING LETTER-WRITING PROJECT!

This is your reminder that if you write me a letter and put it in the mail, I will respond to it with a letter of my own, and send that letter right to you! It really happens! Hundreds of satisfied customers!

Write me at:

Will Leitch

P.O. Box 48

Athens GA 30603

CURRENTLY LISTENING TO

“Wet Dream,” Wet Leg. You should always be suspicious of The Next Big Thing, and I’ll confess that there are probably only four, maybe five good songs on the much-hyped Wet Leg debut record, with the rest ranging from “fine” to “lousy.” (The song about looking at your iPhone too much: Very bad.) But man, those good songs are irresistible. This is my favorite one, with extra bonus points for a Cracker Jack Buffalo ‘66 reference.

Remember to listen to The Official Will Leitch Newsletter Spotify Playlist, featuring every song ever mentioned in this section.

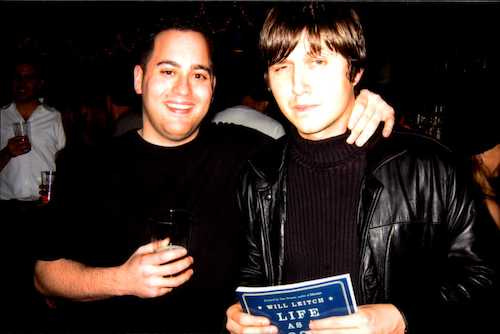

I am not going to inundate you with photos from the Daily Illini 150 weekend last week, but this one should sum it up.

Have a great weekend, all.

Best,

Will

I wonder what you think about a fancy pants writer like Thomas Pynchon who took seventeen years to write another novel after Gravity's Rainbow. What was he doing? Probably living off of a substantial amount of money, but you'd think an acclaimed writer would have the itch more often.

Terrific essay today. I taught writing for a few decades at American University. I used to tell students the story of a friend whose father was a long haul trucker. Never once, my friend said of his dad, did he experience "truck driver's block." (Eager to read the new book -- I'll have my eye out for it.)