Volume 4, Issue 17: Ken Dayley

"You've gotta get back out there and pitch, no matter what happened yesterday."

Here is a button where you can subscribe to this newsletter now, if you have not previously done so. I do hope that you enjoy it.

My sons have taken so many flights at this point that they each have their own frequent flyer number; Wynn, for our trip to Cape Canaveral in a couple of weeks, actually just got upgraded. But my childhood was not one of travel. I’ve never been to Disney World, I didn’t leave North America until I was well into my thirties, I’d only been to Chicago, which is in the same state, once by the time I graduated from high school. The only family trips were ever took were to Cardinals games, which is why I’ve been to Cincinnati, Pittsburgh and Milwaukee multiple times but never, say, the Grand Canyon. And until I was a senior in college, I’d been only been on an airplane once in my life.

When I was in the fifth grade, I went to go visit my grandparents, my father’s parents, Bill Leitch (whom I am named after) and Dorothy Leitch. They briefly retired to Fort Myers, Florida, before deciding they were too far away from their family and hightailing it back to Central Illinois after only a couple of years, and I went out there to spend a week during my school’s spring break. Florida was an impossibly exotic place for a kid from rural Illinois—I remember being awed by all the palm trees, and terrified there would be an alligator around every corner.

But mostly I remember the soap.

My grandparents had many eccentricities, from their constant reusing of paper towels (my grandmother used to wash them in the sink and then lay them out to dry on the counter) to the containers they put their false teeth in (Grandma’s had a figure of an elderly lady in a bikini on hers). But the soap blew my mind. My grandparents famously refused to ever throw anything away, and they were so frugal about their bars of soap that when the soap eroded down into that thin little sliver that bars of soap always turn into when you’re done using them, they would save that sliver and then attach it to other, previously saved, slivers of remaining soap. Grandma would let the soap dry, put them in a box and then, when she had enough of them, she’d wet them, smooth them together and make one big “new” bar of soap. (“Free soap,” she explained.)

(Apparently this is still a thing.)

There was something about this procedure, this creation of a new, terrifying species of soap, this Frankenstein soap, that deeply disturbed me. It felt like a violent disruption of the natural order of things, a human centipede of lye. It was the first thing I asked my mom about when I got home: “What’s with Grandma’s crazy soap?”

My mom smiled. “Your grandmother grew up during the Depression,” she said. “I’m sure her mom taught her to do all that to save every scrap they could. You couldn’t waste anything during the Depression. It’s a good lesson to learn.” It wasn’t a lesson I, or my parents, learned. When we run out of soap, we all just go out and buy some more soap. Sticking old pieces of soap together, or washing and drying your paper towels, didn’t catch on at all. It’s just a sign you grew up during the Depression. Which, now, is probably a sign that you are dead.

******************

It became clear, fairly early on in the pandemic, that this was the biggest thing any of us were ever going to live through. I wouldn’t have thought that. Both my wife and I lived in New York City on September 11, and we’d always assumed, particularly when we moved away from NYC, that that would be the biographical detail our children would always ask us about. After all, what historical event could fathomably be larger than September 11? History had other plans for us: Is it possible that there have been three, maybe four, since then? However many, it’s now clear that the pandemic—the deaths, the disruption, the acceleration of existing societal trends, the way it has altered the lives of every single person on this planet in one way or another, permanently—is foremost among them. When history books—or history cranial downloads, whatever we’re doing in 100 years—look back at this century, the pandemic will be the pivot point, the critical event, no matter what happens next. I have no doubt that my grandchildren, if I’m around to see them, will whisper about Grandpa Leitch living through the pandemic, wow, what must have that been like?

This has led to the question: What will be the things that we never shake from this pandemic? What will be our mangled together bars of soap?

There was a time I thought there might be surface remnants, not dissimilar to the soap and the paper towels. Mom, why does Grandpa Leitch wash his hands for five full minutes?, or maybe a whole generation of people avoiding crowded rooms, basically forever, that sort of thing. But I don’t think that’s going to happen. I thought the pandemic might lead to more casual mask usage, as past public health issues in many Asian countries have done, or perhaps a renewed interest in fields of advanced science, as young people realize just how much a difference those pursuits can make, how many lives could be saved through research, dedication and aptitude. It seems pretty obvious neither one of those things are going to happen at this point either.

Some would argue that the pandemic changed the workforce in a permanent way, with employees understanding their power and demanding their employers be more flexible about allowing them to work remotely, even indefinitely. There are companies that have made this bet, and good for them. But you’ll forgive me for being perhaps a bit skeptical of this as well. In the long term, the balance of power does not tend to bend itself toward workers, and I’ll confess, I suspect more people are eager to go back to the office—are in fact already back there, and have been for quite some time—than the current conversation is actively encompassing. It is also possible I am saying this because I’ve been working out of home since 2005 and am ready for the rest of you to get out of my coffee shops all day—it is certainly possible.

But ultimately: I do wonder how much of this will ultimately last. The pandemic is not over, obviously—cases are back up, again, and the United States just passed the million deaths mark, a truly surreal figure, 325,000 more Americans (so far) than died in the 1918 pandemic—but in a functional way, most Americans have moved on as if it has. (Myself included, if I’m being honest.) This is also natural, I would argue, and is certainly not something that be shamed: People have to live their lives, and expecting them to act the same way in May 2022 like they did in May 2020 (or even May 2021) is unreasonable.

But this is also indicative of the larger issue of Moving On. Part of Moving On is, for better or worse, letting go of anything that reminds us of what we all went through. I have friends who were loyal, devoted mask wearers for almost the entire pandemic who now sneer at the very notion of wearing them. I find myself, because I couldn’t do it for so long, wanting to eat and drink inside even if restaurants or bars offer outside service. You know that feeling you get when you see someone in a movie or TV show wearing a mask, that uh, no thanks, I do not want to be reminded of the pandemic in my popular entertainment, thank you? I totally understand that. We all want our escape to be just that: Escape. I’m boosted, and will get another booster as soon as I’m eligible; my kids, now that they are eligible, will be getting their own boosters this week. We’re all doing the right thing, and will continue to. But we’ve all lived through so much. It does not strike me as reckless or, even unhealthy, to want to have make this period a part of our past. It strikes me as sane.

So yeah: I don’t think I’ll be reciting the ABCs to myself while I wash my hands when I’m in my 80s. I’m still wearing masks on airplanes now, but I’m sure I’ll stop at some point. I bet a lot of this doesn’t end up sticking at all. And maybe that’s OK. In March, Scott Small, director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at Columbia University, wrote an op-ed for the Times titled, “We Will Forget Much of the Pandemic. That’s a Good Thing.” I was moved by this section:

While it is often beneficial to remember the facts of a traumatic experience, sometimes even in pointillist detail, it is equally — if not more — important to the healing process to let the emotional valence of it fade. If we don’t, we can get stuck in total emotional recall, reviving our distress in perpetuity.

Forgetting protects us from this debilitating anxiety not by deleting memories but by quieting their emotional scream. The same is true for more run-of-the-mill emotions. Intuitively, it makes sense that we sometimes need to let go of hurt and resentment to preserve close friendships and that we need to forget in order to forgive. “Letting go” is just one of the many colloquialisms that implicitly nod in recognition and gratitude toward our brain’s forgetting mechanisms … For many of us, particularly those on the front line, some degree of emotional forgetting will be a natural part of living in and moving forward from the pandemic.

We’ll never truly be past this. We’re not truly through it now. But I also do not want to be defined by it, not now, and not ever. I sense that many people feel the same. There are aspects of living through a pandemic that I, and all of us, will never be able to shake. I still think it’s all right to try.

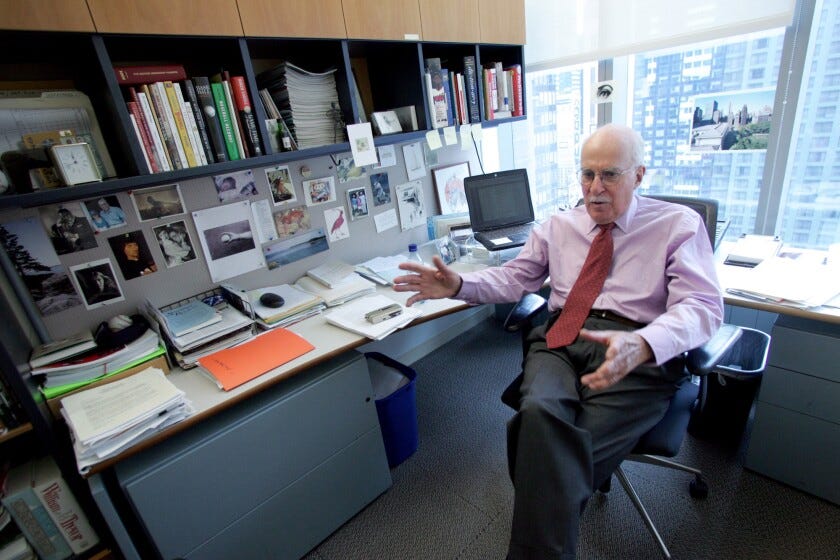

ROGER ANGELL

Roger Angell died yesterday, at the age of 101. As I’ve written, Roger Angell has long been one of my heroes, and it has been heartwarming today to discover just how many of my peers I shared that hero worship with. (I loved this Lindsay Adler piece.) I got to meet Angell once, in a Yankee Stadium press box: I sat next to him for an entire World Series game back in 2009. I didn’t say anything to him, and didn’t bother him. The last thing in the world I wanted to do was mess with Roger Angell’s work.

As a writer, honestly, I cannot think of a life better lived.

Here is a numerical breakdown of all the things I wrote this week, in order of what I believe to be their quality.

Every Stephen King Movie, Ranked and Updated, Vulture. Updated with Firestarter.

Get Your Kids Their Booster Shots Now, Medium. It’s probably more important for them to get one now than it is for you.

The Untouchables, MLB.com. A look at all the guys who haven’t given up a single earned run yet.

Some Simple Numbers About Mass Shootings in America, Medium. We are in the middle of what one might call an “uptick.”

Likely Division Winners, Ranked, MLB.com. I’m honestly sick of the Brewers already.

The Brittney Griner Situation Just Keeps Getting Worse, New York. An absolutely disastrous situation in every possible way.

The Thirty: One Quick Fix For Every MLB Team, MLB.com. I keep writing about how much Tyler O’Neill is disappointing me.

Your Friday Five, Medium. You see, there are five lists. That’s how it works.

PODCASTS

The Long Game With LZ and Leitch, just two shows left. We discussed the NBA Playoffs, Brittney Griner, Jerry Jones and just how much of a miserable prick Michael Jordan was.

Grierson & Leitch, no show this week, Grierson is in Cannes.

Seeing Red, Bernie and I mostly raved about Albert Pujols’ pitching.

Waitin' Since Last Saturday, no show this week.

LONG STORY YOU SHOULD READ THIS MORNING … OF THE WEEK

“How to Build a Twenty-first-Century Tyrant,” Adam Gopnik, The New Yorker. I really wish the tyrants would have waited until after everybody I know and care about were 100 years in a ground before they made their return.

ONGOING LETTER-WRITING PROJECT!

This is your reminder that if you write me a letter and put it in the mail, I will respond to it with a letter of my own, and send that letter right to you! It really happens! Hundreds of satisfied customers!

Write me at:

Will Leitch

P.O. Box 48

Athens GA 30603

CURRENTLY LISTENING TO

“You Will Never Work in Television Again,” The Smile. New Radiohead album? Well, not quite, but absolutely close enough. And this song is about as close as they’re going to get anymore to an old-school Bends/Hail to the Thief joint. This Craig Jenkins review gets the whole album exactly right. (As usual.)

It’s Dog In The Pool season over here …

Have a great weekend, all.

Best,

Will

As soon as I read about your Grandma, I thought "Depression Baby." That's the expression my dad. born in 1930, used. Get every cent out of everything.

I'll miss "The Long Game" - you and LZ are great together! I hope you find a podcast home.