Here is a button where you can subscribe to this newsletter now, if you have not previously done so. I do hope that you enjoy it.

In 2000, for a now-defunct Website I worked on with future fellow Black Table founder Eric Gillin called IssuePaper, I spent a week at the Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles. We had been driving across the country for two weeks at that point, starting in Philadelphia, where we’d covered the Republican National Convention, as part of IssuePaper’s launch. We drove from Philadelphia to Memphis to Oklahoma City to Littleton, Colorado—with a pit stop in Woody Creek, Colorado, where we met up with Hunter S. Thompson to give him a specific kind of road flare he had requested from a random store in the West Village and smoke hash with him—before ending up in Los Angeles to write about the convention. That’s how much money there was in the Internet in 2000. They launched a Website by putting a 24-year-old and a 22-year-old in a rental car with explosives and encouraging them to drive across the country and talk to strangers. That’s the sort of irrational financial exuberance that makes crypto look prudent.

By the time we made it to Los Angeles, even with the infinite stupid energy of a twentysomething spending someone else’s money, we were exhausted. But I was still thrilled. I’d never covered a convention before, and having what was essentially a blank check from an Internet startup (a startup that would shut down a month later, not that I was smart enough back then to see that coming) to write about whatever I thought was happening in America was electrifying. I went to the then-brand-new Staples Center, host of the convention, every morning and just spent all day talking to whomever would talk to me. I tried to go where the energy was.

And the energy was one of protest. This was 2000, before September 11, before Iraq; this was the Democratic National Convention where a young guy named Barack Obama, who had just lost a primary in Chicago by 30 points, couldn’t even get on the convention floor. (“I do always think about the fact that in the 2000 convention, I couldn’t basically get in the hall or on the floor and nobody knew my name,” he said. Four years later, of course, he’d bring the house down and change the trajectory of just about everything in American life, in ways that are still revealing themselves.) The people inside the DNC in 2000 were cozy, surely too cozy. But outside, people were furious.

The big kickoff event of the protests outside the DNC was a Rage Against the Machine concert, held for free right across the street from the Staples Center. I was a big fan of Rage at the time—I was a 24-year-old white male, of course I was—and got there three hours early. I spent all day talking to Rage fans and political activists (there was obvious crossover) and hung out with them after the concert, which, all told, was a little bit of a bust, despite the way the show is now considered in the historical canon. (The band only played four more shows after that one before breaking up … right at the moment that, arguably, their viewpoint was most in need of being heard.) The sound at the show was terrible, you could barely hear any of their songs if you weren’t standing right next to the stage, and the arrests and tear gas that ensued afterwards was less putting down a riot and more, from what I saw, a conflict that mostly arose from some extremely overexcited police officers and a smattering of peripheral dipshits.

But this was a terrific place to meet the people I’d be hanging out with an interviewing the rest of the week. I mostly spent it with two people, whose names I do not remember (and I’d changed back then for my stories anyway) but we’ll call Jeff and Daphne. They were there to protest, and they were organized. Jeff was scruffy and goateed and tall and good-looking and extremely earnest; he considered himself the backbone of the movement and spent most of his time not on the streets, but back at the protestors’ unofficial headquarters, cooking food, laying out cots, making sure everybody had water. Daphne, who had traveled with Jeff from Philadelphia, was a part of all the marches. She would spend most of the day working on the giant puppets they’d take through the streets of Los Angeles, painting them, fixing the rips from the night before, planning out the schedule for the next day’s events. There were many incredible protest puppets at the 2000 DNC. It might be what I remember more than anything else.

Jeff and Daphne were young, even younger than me, and they were devoted to their causes in the way young people are often dedicated to their causes: Fervently, if a bit fuzzily. They believed absolutely, and whole-heartedly, that they were making a difference and that they were on the side of right. I just was never quite sure what exactly their side was. Their causes were, in fact, a bit hazy even back then. There was talk of globalism, and government censorship, and Occidental Petroleum, and Mumia, oh, yes, lots and lots of discussion of Mumia. But the overall message was not one of despair or even, you know, rage. The protests were not that the country was not progressing; it was that it was not progressing fast enough.

The understanding—and this was my understanding then as well—was that history was always moving forward, and that the Democrats were just as responsible as Republicans for slowing that progress. It was taken as a given that the rights we already had, rights that people had been fighting for for decades, were now locked in, that the only way to continue to move was forward. People were not protesting because they were afraid of losing something; they were protesting because they, very reasonably, wanted more. They saw some demons on the horizon—this was the first place this 24-year-old kid from the Midwest was introduced to the notion of radical anti-capitalism—but it was undeniable that the protests were about moving forward rather than hanging onto the victories they’d already achieved. Those were locked in stone, immutable; they were accepted like air. The anger at the people inside Staples Center was for being on the wrong side of history … but that history was about what should happen next, not what already had been settled.

It was protest out of hope, not fury. All the protestors—I remember this more than anything—were so, so nice. I recall Jeff telling me, “the people in that building don’t understand, and we have to do what we can to try to help them understand,” and it was the word help that stuck out. He really just wanted to help. He was absolutely certain he was correct in his convictions, and I was absolutely certain he was right too … though I’m still not entirely sure, 22 years later, precisely what those convictions were.

But I do remember one thing loud and clear, the overarching viewpoint, the driving ethos, the one thing everybody there agreed on, from Jeff and Daphne to all the protestors back at headquarters to Rage Against the Machine themselves: There was no difference between Democrats and Republicans. They’re all the same.

That was the thesis statement of the whole week. Democrats and Republicans are the same, all part of the same corrupt system. Maybe Al Gore would win. Maybe George W. Bush would win. It didn’t matter. “It won’t change your life at all, either one,” Daphne told me. There are two puppets that week I remember particularly vividly. One warned of the dual-headed menace, the “Billionaires For Bush or Gore” puppet, which positioned the men as two sides of the same coin.

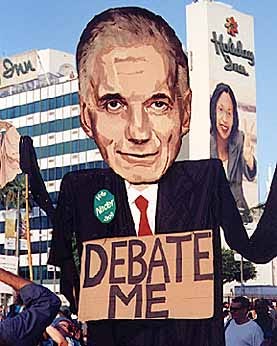

The other was one Daphne was working on, one of Ralph Nader, the Green Party candidate for President. A common protest that week centered around the two parties not inviting Nader to any of their debates. When Gore took the stage to accept his nomination—and eventually do that terrifying kiss with his wife Tipper, and by the way, pretty wild that of the marriages on the 1992 and 1996 Democratic tickets, that’s the one that ended in divorce—they rolled out the “Debate Me” Nader puppet.

And that’s what those protests were really about: That there was no difference between Gore and Bush: Between Democrats and Republicans. “Our democracy has been hijacked!” Zack de la Rocha screamed from the stage, not that I could hear him at the time. “Our electoral freedoms in this country are over so long as it’s controlled by corporations! We are not going to allow these streets to be taken over by the Democrats or the Republicans!” I understand the sentiment. I got it then, and I get it now.

But.

But of all the things that haven’t aged well from 2000—and remember, this is what a computer looked like in 2000—I can’t think of a worse one than that. I actually heard some of the same loose talk 16 years later, when it was even more wrong. As I look around today, I look at the rubble of so many of those rights that Jeff, and Daphne, and Al Gore, and Barack Obama, and Ralph Nader, and me, rights we all took for granted back in 2000, and see them stripped away by radicals purposely subverting the will of the vast majority of the American people, and they’re just getting started, as I stand jaw agape at how backwards we’ve gone in such a rapid period of time … you know what? I’m pretty sure there’s a difference. I haven’t learned much since 2000. But I’ve sure as shit learned that.

Here is a numerical breakdown of all the things I wrote this week, in order of what I believe to be their quality.

Nobody Cares About Elvis Anymore, Medium. Sorry, they don’t care about Pavement either.

The Brooklyn Nets Have Turned Themselves into the Knicks, New York. It happened so slowly, then so quickly, that hardly anyone noticed.

Guys Getting a Raw Deal in All-Star Voting, MLB.com. Sticking up for Tommy Edman, Juan Soto and Jeff McNeil.

The Heart Vs. Stats All-Star Debate, MLB.com. Two ways of filling out a ballot.

Your Friday Five, Medium. Five is the loneliest number.

Five Lessons From Finally Getting Covid-19, Medium. A bit of a rehash of last week’s newsletter, all told.

PODCASTS

Grierson & Leitch, four big movies: Lightyear, Spiderhead, Good Luck to You Leo Grande and Cha Cha Real Smooth.

Seeing Red, Bernie and I talk about a team that was once in first place.

Waitin' Since Last Saturday, we did our big “have a nice summer!” episode.

LONG STORY YOU SHOULD READ THIS MORNING … OF THE WEEK

“I’m Full,” Adam Platt, New York. I am not an avid reader of food writing, I must confess, which is my problem, not food writers’. But I always loved reading my friend Adam, who was funny and weird and big-hearted and hopeful. This is his goodbye after 22 years at New York. (Only eight more than me, if you can believe that.) I am sure Adam will continue to smoke me in the New York fantasy baseball league.

Also, definitely Rebecca Traister: “Hope is a discipline.”

ONGOING LETTER-WRITING PROJECT!

This is your reminder that if you write me a letter and put it in the mail, I will respond to it with a letter of my own, and send that letter right to you! It really happens! Hundreds of satisfied customers!

(I know I am behind on these, but I’m catching up next week.)

Write me at:

Will Leitch

P.O. Box 48

Athens GA 30603

CURRENTLY LISTENING TO

“Elvis Is Everywhere,” Mojo Nixon. Elvis needs boats! Elvis needs boats!

Remember to listen to The Official Will Leitch Newsletter Spotify Playlist, featuring every song ever mentioned in this section.

Be safe out there. Whatever we do, we gotta do it together.

Best,

Will

Today, of all days, as women's clinics close throughout the South and Plains, you choose to indulge in hippie-punching, instead of attacking the "radicals purposely subverting the will of the vast majority of the American people". Christ, Will.

The main difference between Democrats and Republicans is that Republicans care about results, not process. So many Dems think people care about fair play, and doing it "by the books.". Shouting at bad faith actors on the other side of the aisle that Merrick Garland got robbed isn't going to do shit, when people are losing their rights. Play it dirty, or don't show up, the base of the party is weary of "civility."