Here is a button where you can subscribe to this newsletter now, if you have not previously done so. I do hope that you enjoy it.

This week, I listened to a podcast interview with former Vice President Al Gore by David Remnick, the editor of The New Yorker. (You can read an edited version of the transcript right here.) The interview itself is interesting, if not particularly revelatory: All these years later, Al Gore remains a guy who is generally right about everything but still has a way of making you feel like a schlump about it, a professor you begrudgingly admit learning something from but still talk shit about constantly. But there’s a moment in which Gore, in his dopey, voice-of-how-a-horse-would-talk-if-a-horse-could-talk fashion, had me cheering.

The premise of the interview is that Gore, after being years ahead of the rest of us on the climate crisis, not only refuses to boast about it but in fact makes a hopeful case for the environment. At one point, he says, “we’re gaining momentum so rapidly that I’m convinced we will soon be gaining on the crisis itself.” Remnick, far more of a doomer on this topic (and many others) than Gore, pushes back, noting that New Yorker writer Elizabeth Kolbert is constantly describing a far gloomier climate future. Gore, who calls himself “temperamentally optimistic,” doesn’t start a fight with Remnick or Kolbert, or directly refute them, or even necessarily call them wrong. He just says that their despair on the topic—and their despair in general—isn’t helping anyone. Not just that: It’s actually hurting.

“The old cliché ‘Denial ain’t just a river in Egypt’ should be joined by ‘Despair ain’t just a tire in the trunk,” Gore says, in an extremely Al Gore joke construction. “Despair is just another form of climate denial. We don’t have time for it. The stakes are so high. … We have to act. We have no choice, really. … We don’t have time to wallow in despair. We’ve got work to do, and the stakes have never been higher.”

We don’t have time to wallow in despair. Gore laments later in the interview that he’s not the most inspiring speaker, that he “wish[es], so deeply, that I could find the words to inspire in others the burning passion for saving our country.” But I think those are the words right there: We don’t have time to wallow in despair. What a phrase. It combines what I believe to be the two most important personality traits for a person to have, the two things I hope, more than anything else, to instill in my children: Hopefulness, and urgency. You need to believe that life can be good, and you need to believe it right now.

This does not mean that you pretend the world is some sort of perfect place. It doesn’t mean hectoring other people if they don’t agree with every word that you say. It doesn’t mean sticking your head in the mud—or turning on Netflix and hiding—every time something terrible happens. It means the opposite of all that. It means understanding that the world is hard and awful things happen and people can be monstrous and that it can all feel like everything is conspiring against you … and still getting up and fighting for things to be better anyway, fighting for the things you care about, fighting for the people you love, fighting for the ideals you aspire to and, most of all, fighting for yourself.

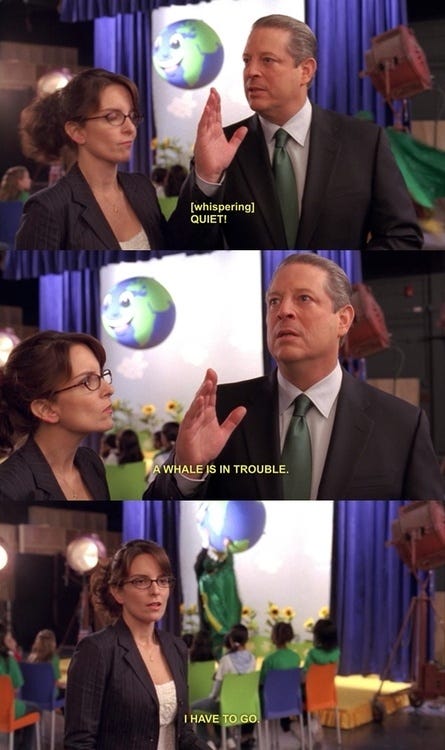

It means, at its core, that you can’t give up. Listen to Al Gore. A whale is in trouble.

One thing I was extremely wrong about when I was younger was that I thought life would get easier as I got older, rather than harder. More to the point: I thought it would get simpler. I thought once I got the big questions answered—What would I do with my life? Would I find a job? Would I build a career? Would I get married? Would I have a family?—the world would clarify itself. Sure, life would still be challenging, and I’d have moments of sadness or worry and anger and fear and all that comes with being alive. But I thought there would be a point where I’d turn the corner, where I’d think, “OK, whew, I made it. Now I can breathe a little.”

This is a question I’m regularly asked by people just starting out in their careers, a familiar question because it’s the same question I asked “established” adults when I was just starting out: How do you know you’ve made it? “Made it” is always the key phrase, because when you are young, that’s what is pounded into your brain: You’ve got to “make it,” whatever “it” is. Your parents are on you about it, your friends are worried about it, your entire focus is on building toward it: You have to “make it.” When I am asked this question, this “how do you know you’ve made it?” I give the same answer, the obvious one, the only honest one: “You don’t. Ever. I haven’t made it. I’ve never felt like I made it. And I am sure I never will.” This is the same answer adults gave me when I asked this question when I was young, and it’s the only sane one. You never turn the corner. You never get over the top. You’re constantly hanging on for dear life. I don’t know this when I was younger. I’m glad I didn’t know this when I was younger.

But I’ll confess: I’m also glad this is the case. I wonder if one of the most important lessons is that you should never get too comfortable—that if you’ve stopped being engaged, you stop learning or growing or being engaged with anything at all. If I’ve been surprised by one thing from many people my age as we’ve navigated our 40s, it’s a creeping disengagement from the world: The growing sense that the world is bad, that it’s getting worse, that there’s nothing we can do about it, and therefore getting yourself worked up about it, or thinking you can somehow change it, is foolish—wasted energy. You see this manifest in many ways and many worries: Trump’s going to become President again, but worse this time (my personal most pressing worry, and it should probably be yours too), the horrible situation in the Middle East will expand in a more global instability and violence, the extremists of our society are taking up more and more of the oxygen and gaining more and more of the power, that none of this matters because the planet’s going to be unlivable in 50 years anyway. These frets mount, they pile up, they lead to a sense that the world is careening out of control … that it’s all falling apart. They lead to despair. They lead to giving up.

But that is an abdication, not just of the duty we have to the world around us but also to ourselves. We don’t have time to wallow in despair. That’s true in Al Gore’s context of the climate crisis, but it’s also true in the timeline of our lives: The time we have on this earth is so finite, and so valuable, that giving up is selling ourselves short. Life is not about numbing yourself into apathy, or pretending that the world inside of your home isn’t directly affected by what happens outside of it. Life isn’t deciding that politics is stupid and unimportant because someone did something you don’t like or because “they’re all the same.” Life isn’t pretending that if you shut out the noise, the noise isn’t there. Life isn’t checking out. Life is being engaged. Life is being out there and taking part, about lacing them up and getting in the game. About believing what you do matters. Being hopeful. Being urgent. We ain’t here forever. I’m not going to waste the time I have slumping my shoulders. I don’t have have time for despair. You don’t have time for despair. None of us have ever “made it.” There is always work to do. So let’s do it.

Here is a numerical breakdown of all the things I wrote this week, in order of what I believe to be their quality.

Breaking Down the Four Possible World Series Matchups, MLB.com. All right, stop what you are doing, because I’m about to ruin.

Your Up-to-the-Minute MLB Power Rankings, MLB.com. The image and the style that you’re used to.

Previewing Thursday’s MLB Playoff Games, MLB.com. I look funny, but, yo, I am making money, see.

Previewing Wednesday’s MLB Playoff Games, MLB.com. So, yo, world I hope you are ready for me.

Previewing Tuesday’s MLB Playoff Games, MLB.com. Now gather around, I am the new fool in town

Previewing Monday’s MLB Playoff Games, MLB.com. And my sound is laid down by the Underground.

Previewing Sunday’s MLB Playoff Games, MLB.com. I will drink up all the Hennessey you have on your shelf, so please let me introduce myself.

PODCASTS

Grierson & Leitch, we discussed “The Exorcist: Believer,” “The Royal Hotel” and “Fair Play.”

Waitin' Since Last Saturday, we recapped Kentucky and previewed Vanderbilt.

LONG STORY YOU SHOULD READ THIS MORNING … OF THE WEEK

“Your Moral Equation Must Have Human Beings on Both Sides,” Jonathan Chait, New York. This is what writing precisely, carefully, honestly and humanely looks like.

Also, I watched a movie this week about John Allen Chau, the missionary who was killed trying to proselytize to an isolated tribe off the coast of India back in 2018, and I’m so fascinated by the story, and the larger context, that I can’t stop reading about it. Here’s a great primer on it.

ONGOING LETTER-WRITING PROJECT!

This is your reminder that if you write me a letter and put it in the mail, I will respond to it with a letter of my own, and send that letter right to you! It really happens! Hundreds of satisfied customers!

Write me at:

Will Leitch

P.O. Box 48

Athens GA 30603

CURRENTLY LISTENING TO

“Meant to Be,” Wilco. OK, after a couple of weeks of listening, I’ve decided that while I like the new Wilco album Cousin, I find it oddly muted, as if it is so exhausted by the world that it can only muster up the energy to shrug. I found myself thinking, “yeah … they’re not going to play any of these songs in concert in 10 years.” I still like it, though, and this is my favorite song off it.

Remember to listen to The Official Will Leitch Newsletter Spotify Playlist, featuring every song ever mentioned in this section.

Also, now there is an Official The Time Has Come Spotify Playlist.

We got the Waitin’ Since Last Saturday crew together this week and dressed up all nice for the occasion.

Also, we enjoyed some early—very early—soccer this morning.

Have a great weekend, all.

Best,

Will

Thank you so much for this.

My name is Humpty, pronounced with a Umpty.