Volume 5, Issue 2: Big Girls Don’t Cry

"Imagine being an architect who's never lifted a stone."

Here is a button where you can subscribe to this newsletter now, if you have not previously done so. I do hope that you enjoy it.

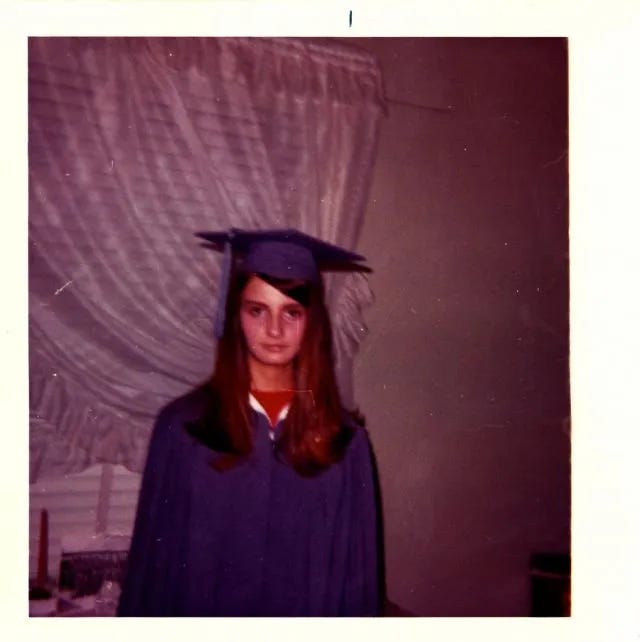

My mother was 18 years old when she met my father. She was a student at Lake Land Community College in Mattoon, Illinois, studying for associate degree in physical education, and she had only been out of her hometown of tiny Moweaqua for about nine months. She was sitting home by herself when my father showed up, hours late to pick up her roommate for a date. They got to talking. He was about to ship out for basic training; he’d enlisted after graduating from high school and assumed he’d be going to Vietnam soon. She was taking classes, away from home for the first time. Mom once told me all she knew about him was that he had a nice car and looked good in his uniform. That was enough. They were married a year-and-a-half later; he drove up from Langley Air Force Base in Virginia for the weekend, got hitched and then drove back. She met him down there after she graduated. Two years after that they were back in Mattoon. Two years after that I showed up. Five years after that, my sister did. It happens fast.

Mom was smart. Everyone in her family had always known that, that’s why she went to college in the first place—hardly an assumption at the time, particularly for a young woman in 1970. (Neither my father nor any of his seven siblings ever went to college. No Leitch boy would enroll in college until I arrived at the University of Illinois in the fall of 1993.) But Mom, for all her smarts, was still just a teenager, without any real direction or specific passion, and this Bryan guy seemed like a nice guy and there was that car and that uniform. So she just went with it. She raised me and my sister while Dad worked at Young’s Construction, and then Dad, with his bare hands, built us all a new house to live in. It was a good life, but money started to get a little tight, so Mom started taking odd jobs to bring in some extra income. She took some shifts as a waitress at Monical’s Pizza downtown, she filled as a second-grade substitute teacher, she even worked on the night shift on an assembly line at General Electric for a couple of years, putting light bulbs in those little boxes for 10 straight hours. She found she liked the work, liked being a part of something, liked being out of the house—liked being useful. But something nagged. She felt she had more to offer the world. No: She knew she did. She had smarts. But she had never gotten to use them, not really. There had to be something.

So, at the age of 34, with a 10-year-old and a five-year-old, she decided to start over. She sat down with my dad and let him know: I need more. She wanted to go back to school. She wanted to be a nurse. She thought she’d be good at it. She thought she could help. Dad wasn’t sure. Aren’t we already overwhelmed? Can we really afford to pay for college? Mom made it clear that this was not a matter up for discussion. She was smart. She wanted to go be smart.

Thus, my mother, in the middle of the madness of raising two children, went back to college. She returned to Lake Land, which she now lived about a-mile-and-a-half away from, and created a routine of getting the kids ready for school, sitting in class all day, sprinting back home to arrive before the bus dropped them off, scraping together dinner, putting them to bed, staying up half the night to study. She loved the studying—the learning, getting to (finally!) use that smart brain. She earned her LPN in two years, got straight A’s next to students half her age, and then decided, well, that’s not enough: I want more. So she applied to the University of Illinois’ Registered Nurse program, driving the 45 miles up and down I-57 to Champaign every day, sometimes even taking her children with her to sit in the back of class if she didn't have anywhere else for them to go that day. I remember, in middle school, her coming into my bedroom before I went to sleep and having me quiz her the night before tests. She would also practice IV’s on me, lightly poking me in the wrist with the needle until she finally found the vein. She got straight A’s in Champaign too.

Then … she was a nurse, and that was that: That was who she was, from then on. The next 25 years of her life, she worked at Sarah Bush Lincoln Health Center, in the emergency room, taking care of strangers during the worst moments of their lives. She would end up running that ER for a decade, the first person everyone, from doctors to other nurses to orderlies to patients to drug reps to cops to insurance hacks to hospital executives, all went to when they needed to find out what was really going on—how to get a problem fixed, how to get shit done. She also took care of the people she loved, both inside that hospital and out; for decades, whenever a co-worker, a friend or anyone in our extended family has had any sort of medical issue, from a fatal diagnosis to a nagging hangnail, they’ve always called Sally to find out what she thinks they should do. She retired almost seven years ago now, and but that hasn’t stopped any of us: She is always on call. It is impossible to think about my mother without thinking about her work as a nurse. It is an inextricable part of her, professionally, personally, emotionally, structurally. It’s who she is.

But for half her life, that’s not what she was at all. She was something else, something she was dissatisfied with—not unhappy, not miserable, but just dissatisfied. She knew there was more out there for her. And—and this is the important part—she went out there and got it. She was 34 years old, and had all the momentum of the world, of her world, stacked against her. She had every reason to sit still, to put her ambitions behind her, to feel like maybe she hadn’t quite reached the ceiling of what she was capable of but was still living a perfectly fine life. But she didn’t sit still. She knew what she wanted to do. So she decided to do it. It didn’t matter that it was difficult. It was better that it was difficult. She wasn’t going to let it be too late to do what she wanted to do—ever.

It was inspiring, then and now, and, as her son, it is certainly not a coincidence that I always find myself most comfortable around people like her, people who can’t sit still, who don’t get too comfortable, who are always pushing to find that truest version of themselves, to find that place they’re supposed to be. It’s how I finally got my own career going well into my 30s; it’s how my friends have made dramatic, wildly successful career turns later in their life; it’s how my wife started her career over after having children and now has employees who, like her, walk into an office everyday that has her name on the door. These are my favorite type of people: Restless people. People who are always searching, who are never content, who are still intellectually and emotionally curious, who are yearning for something and won’t stop trying to nail down precisely what it is—and then getting down to work at making it happen.

They didn’t quit. They didn’t sit around lamenting all things they’d always wanted to do. They didn’t think the best parts of their lives were behind them. They knew their worth, even if the world didn’t, not yet. They kept pushing. And then they got what they wanted. And the rest of us, all of us, were better for it.

My mom still has this quality. She always will. A few years after she became a nurse, she had a spiritual awakening that inspired her to research all the world’s religions, so she could decide which one fit her the closest; it may surprise you to learn she landed on Catholicism, which has provided her peace, comfort and solace through personal turmoil, the loss of loved ones and a successful fight against breast cancer. After she retired, she and her husband decided to uproot the only life they had ever known in Illinois and move down south, to be near their only grandchildren; she now is a fixture of her church and the local YMCA, runs multiple book clubs and is on the board of her local library—an assignment that has gotten strangely intense in the last couple of years, but one she’s very much up for.

And in the last few years, she has become a runner, regularly running 10Ks throughout Georgia, constantly winning her age group. She actually just ran one this morning. She won again. I went with her. I’ve become a runner later in life too, after all.

Our lives are long, longer than we realize. There are always many roads forming ahead of us. The world can hang on our shoulders, drag us down, make us tired, too tired, to remember who we are, what drives us, who we have always known ourselves to be. But Mom, that scared but determined 34-year-old Sally Leitch, reminds me that there is always time. No matter how old you are, no matter how stuck you may feel, no matter how many obstacles may stand in your way, you can still keep yearning, and searching. You might just, like my mom, like so many others, find what you were looking for. You may find where you belonged all along.

Here is a numerical breakdown of all the things I wrote this week, in order of what I believe to be their quality.

My Writeup from the National Championship Game, New York. In the future, we’ll all be Michigan, and only Michigan.

Your Next 10 World Series Winners, MLB.com. One of these days I’m going to get one of these right.

Your Blake Snell Power Rankings, MLB.com. I’d like the Cardinals to stay out of this one.

PODCASTS

Grierson & Leitch, we’re back tomorrow night, so you should listen to Dorkfest one last time.

Waitin' Since Last Saturday, we did our annual end-of-season Feelings Episode.

Seeing Red, no show this week.

LONG STORY YOU SHOULD READ THIS MORNING … OF THE WEEK

“This Might Be the High-Water Mark for Trumpism,” Jonathan V. Last, The Bulwark. Some optimism, coming in handy. You can get a lot of that here as well.

Also, here is a funny (and of course sad and terrifying) piece about how much worse Trump has gotten, like, cognitively, in the last four years.

Oh, and I’ve been waiting for someone to write about the post-pandemic chronic absentee problem in public schools—something I see constantly here in Athens—and voila, here’s a terrific New Yorker piece about it.

ONGOING LETTER-WRITING PROJECT!

This is your reminder that if you write me a letter and put it in the mail, I will respond to it with a letter of my own, and send that letter right to you! It really happens! Hundreds of satisfied customers! I am caught up on anything sent in 2023 now, so if you haven’t gotten a response, it got lost, send me another one!

Write me at:

Will Leitch

P.O. Box 48

Athens GA 30603

CURRENTLY LISTENING TO

“Right Between the Eyes,” The Bloody Hollies. In honor of the Buffalo Bills, the official 2024 postseason team of The Will Leitch Newsletter (with love to William’s Browns of course), here is Buffalo’s own The Bloody Hollies. This song makes me want to jump through a table. Also: What a great name for a punk band, The Bloody Hollies.

Remember to listen to The Official Will Leitch Newsletter Spotify Playlist, featuring every song ever mentioned in this section.

Also, now there is an Official The Time Has Come Spotify Playlist.

Have a great weekend out there, everyone. Happy MLK Day, let’s all go out and there and try to help some people.

Best,

Will

Wow, Will, an amazing and inspirational story!

I too love people who push themselves to be more, do more, learn more, experience more. Your mom is inspiring. Thank you for sharing her great story.