Volume 5, Issue 22: Second Opinion

"One thing you can never say is that you haven't been told."

Here is a button where you can subscribe to this newsletter now, if you have not previously done so. I do hope that you enjoy it.

The winner of this year’s The Will Leitch Newsletter women’s basketball pool was “RSpuhler.” That winning entry, which as you will remember comes with the reward of an assigned newsletter topic, came from Robert Spuhler.

Here is what Robert asked me to write about:

I'm sure you've written about this at some point in the past, and if it feels repetitive, let me know, but here's what I've got. Over the last number of weeks I’ve had the chance to hangout with a few out-of-town friends of mine who were visiting Los Angeles and, over a drink or two, the conversation so often comes around to how this moment feels so existentially unsettled. I thought it was just me, as a writer holding on to his profession by a thread (while supplementing income via tutoring) and watching private equity essentially tell me that the thing I’ve trained myself to do since fifth grade is surplus to requirements. But one is in marketing and has his eye trained on his company’s stock price as if it was a capitalist Sword of Damocles, and my other friend sees a gridlocked political system that passively accept homelessness, disease, and war, and worries that a breaking point is coming.

Do you think this is a particularly unsettled time? Or is that feeling tied to growing older and being more aware of the wider world? Do you feel it, ever? And if you do, what do you do?

(Did this turn too much into Dear Abby?)

So, fun one this week! Thank you, Robert. Here is your assigned newsletter topic, something I have indeed been thinking a lot about myself. Congratulations on your victory, I don’t know why we all didn’t pick South Carolina.

************

There was an amazing moment during the 2019 Golden Globe Awards that I think about all the time. Andy Samberg and Sandra Oh were the co-hosts that year, and in their opening monologue, they touched a bit on each of the films nominated for Best Picture. One of those of those films was Black Panther.

Here is what Samberg said:

You really should watch Samberg’s delivery, but in case you’re on your phone, here’s what he said:

“If you told me as a kid, growing up in the Bay, there'd be a movie called Black Panther that starts off in Oakland, this is not what I would have imagined," Samberg said, then addressed Black Panther director Ryan Coogler directly. "Ryan, were there, like, a bunch of old members of the actual Black Panther Party saying, 'I can't even get an audition?' Just kidding, they were all framed and murdered for wanting justice and equality. The world is and always has been a nightmare; it just seems worse now because of our phones … so, what else happened this year?”

It’s a terrific comedic moment, even more so for the anger and helplessness hidden just underneath; it nods to the notion that we are living in unprecedentedly perilous times full of injustice—and here is your reminder that this took in January 2019, before the pandemic—while reminding us that this has been going on forever: We’re just more aware of it now. (It’s also a great way to bring more attention to the fact that what Samberg is saying is absolutely true.) But it also raises the question that Robert is referring to in his question, albeit in a backwards way: Are we living in unusually unsettled and awful times, or does it just feel that way because we have unprecedented ability to access all the awful things that happen (and can immediately communicate our despair)?

Is this the worst it has ever been? Or does it just feel that way?

I find myself coming down on both sides of this debate, so rather than give a definitive answer to Robert’s question, I’m going to make the case for each side. Are we living in a historically unsettled and dangerous time? Or are we just looking at our phones too much?

THINGS AREN’T NEARLY AS BAD AS THEY SEEM, RELAX

In the macro, circumstances are better than they have ever been.

Matthew Yglesias has written persuasively about the fundamental fact—and it is a fact—that Americans live in what is “indisputably one of the richest countries on the planet, at a time of unprecedented global prosperity.” This is not the case for everyone, obviously, just as it has never been the case for everyone; there will always be people who are unfairly struggling as there will always be people who are unjustly thriving. But on the whole:

Global poverty is down dramatically over the last 30 years.

Violent crime has fallen 50 percent in that same time.

We have doubled our life expectancy since 1900.

Fewer people (by percentage and in total) are dying in wars than any other time in human history.

There are many, many more examples that make a compelling argument that we may be living in the best of times. Overall, people are living longer, they are living wealthier, they are living safer, than during any other age in my lifetime. This does not mean all problems have been solved—far from it. But it does make a strong case that this is not the worst things have ever been, no matter how it may feel.

We really do think everything is worse because of our phones.

One of my big media theories is that when everyone is complaining about “the media,” they’re really complaining about themselves.

“News,” such as it is, is fundamentally about change, and always has been: Dan Rather never came on the “CBS Evening News” and said, “Today’s top story: Everything’s fine, don’t worry about it, nothing has changed, go back to your dinner.” News is what is different today from what it was yesterday. It’s about change. When we yelled at Dan Rather, or our local newspaper, or “the media,” it was, at its core, because we were comfortable how things were, and we were thus mad at them because they were informing us that those things were about to no longer be like that. Media by definition focuses on bad news, or at least new news: Most headlines boil down to HEY, EVERYBODY, LOOK AT THIS THING THAT JUST HAPPENED THAT MAKES THE WORLD DIFFERENT. People don’t like new news. They want things to be like they are and how they understand them. They want to be left alone.

As social media has taken over most aspects of human discourse, we have all, essentially, become members of the media. We point out things that provoke us, or confuse us, or disorient us, and we broadcast them to everyone in our orbit. And we thus do what the media has always done: We point out the new stuff—usually the bad stuff. Thus, every time you pick up your phone and scroll through whatever social media platform you use, that’s what you see. Of course we think the world is terrible: The only media that truly engages us, that grabs us by the lapels and demands your attention, is bad news.

This is what Samberg was saying: He was saying things have always been terrible, we can just see them all the time now. He used this example not as a defense of the way things are but rather as an indictment of the past, but the point stands either way: Things aren’t unusually horrible now, but the way we consume media, and the access we have to horrors we didn’t have access to before, absolutely can make it feel that way. This is one of the main frustrations the Biden campaign keeps running into. A large percentage of the problems that people are constantly complaining about have been directly addressed by the Biden administration, with considerable, if still tentative, results. There are concrete ways that the world is better than it was when Biden took over. But it doesn’t feel like it.

Jonathan V. Last got at this, albeit in an angrier way than I might have, when he wrote about the reaction to the Trump verdict yesterday, in The Bulwark.

It would be nice to believe that a felony conviction will cause the scales to fall from the eyes of American voters. That over the next 20 weeks the public will realize that Donald Trump is manifestly unfit for office.

But we wake up this morning and the American people are still the same people.

55 percent of them think the economy is shrinking, when we’re actually the envy of the world.

49 percent think the stock market is down when it’s at historic highs.

49 percent think unemployment is at a 50-year high, when it’s at one of the lowest sustained levels, ever.

These are not the views of people who live in the real world. They are the views of a decadent people who believe that they have the luxury to play make-believe with political life.

I think there’s something to be said about the “decadence” he’s talking about there, but I also believe it’s simpler than that: We have chained ourselves to devices that are built to terrify us and make us believe everything is on fire. Thus that is what we believe.

You start thinking more about the world’s faults, and your own anxieties, as you get older.

Robert hits on something in his question: Is that feeling tied to growing older and being more aware of the wider world?

I was getting the boys ready for their soccer camp on Friday morning while watching “Morning Joe” talk about the Trump verdict, hoping the boys would soak in the historic moment. But of course they weren’t soakin in anything: They were just mad I’d turned off “Brooklyn 99.” (Which they are currently obsessed with, for good reason, that show is great.) And that is what they should be doing. They’re young. They’re kids. The last thing I want for them is to be emotionally paralyzed by politics and global instability. They should be watching funny shows and playing sports and laughing with friends and rolling around in the grass.

I grew up during the Cold War, a time of tension and uncertainty, but I don’t think of my childhood that way at all: I think of baseball and playing tag with my friends and jumping in swimming pools. That is the privilege—really, the sacred right—of youth, and it’s one that can’t help but fade as we get older. With age comes responsibilities, and fears for the future, and experiences of loss: You can’t really prance around the world like it’s your playground anymore. The world always seems more dangerous and unsettled because it’s now your world.

I remember, when I was 10, seeing a television program called “The All-Star Tribute to Dutch,” a (rather remarkable) celebrity event honoring Ronald Reagan. I pointed it out to my dad at the time, and I vividly remember him saying, “Yeah, they’ll all be singing to him when the bombs are coming down!” Dad was surely reacting to a scary story he’d seen on the news, of the fears of nuclear war that were so prevalent at the time. (And also a little stressed at work, apparently.) Why wouldn’t he be thinking about those things? He had a 10-year-old son and a five-year-old daughter, and he fretted for the world that awaited them. But my sister and I weren’t thinking about that. We were kids. Worrying is for adults.

Unfortunately: We’re adults now.

THINGS REALLY ARE THIS UNSETTLED, YOU’RE RIGHT TO BE WORRIED

The world really is on fire, like, literally.

A little part of me changed forever when I read my friend and former editor David Wallace-Wells’ notorious piece “The Uninhabitable Earth” for New York back in 2017. (Later turned into a best-selling book, one of the two deeply depressing books in which I show up in the acknowledgments section—this is the other.)

It was impossible to ignore any longer: At some point, if we don’t turn things around (and maybe even if we do), this planet will no longer be a place where humans can safely live. This is not a theoretical issue, not any more; it’s one that my children, and their children, will have to face head-on because of the mistakes of my generation and the generations before mine. It is one thing to say, “my children will live in a scary world.” It is another to say, “my children won’t even have a scary world to live in.” I cannot say with certainty that my great-grandchildren will be able to safely live on earth.

Kids grow up today with this implicit understanding of what could be in store for them. Sure, there’s less violence, and less poverty, you tell yourself whatever you need to tell yourself. The world by definition can’t be better if you can’t live there anymore. How could you not despair?

We can’t agree on any base level of truth.

I saw a lot of people react to Trump’s conviction on Thursday by saying the upcoming Presidential race couldn’t help but be shuffled by all the headlines screaming “TRUMP CONVICTED.” They were often accompanied by photos like this:

Now: I love newspapers. I have boxes and boxes of newspapers and magazines I’ve written pieces for in my basement, and I cherish them. I very much miss sitting down on a Sunday morning and devouring the paper cover to cover. But I don’t do that anymore, because no one does that anymore, because that is not how people consume their news anymore. They just read their feeds. And their feeds tell them exactly what they want to hear.

This is another issue the Biden campaign (and journalists in general) are having: Getting people to accept basic human facts. You saw this with the financial numbers I mentioned above, but really you see it with everything. The reason we are so polarized, the reason we can’t agree on anything, is that we do not co-exist in some universally accepted monoculture anymore: The information we receive is so specific to our own media ecosystem that we not only don’t have to come up with defenses against opposing arguments anymore, we don’t even have to be confronted with them in the first place. There is a huge percentage of this country that lives on an entirely different plane of reality than I do. There is no talking to them, or reasoning with them. They have their minds mind up to believe only what they choose to see.

And you know what? They’d say the exact same thing about me, and everybody else.

We have always had disagreements. But our disagreements are no longer about policy, or value systems, or even morality: Our disagreements are about what is true and what is not true. I don’t know how that problem gets fixed. I have no idea how you even start.

Trump.

I am not going to go on a long dissertation about Trump here, if just because it’s exhausting and because I’ll save a lot of it for my bi-annual election endorsement piece coming in a few months. (I do these every two years. Here’s 2022’s, and 2020’s, and 2018’s, and 2016’s. I’ve been doing this newsletter for a while!) But the simple fact remains: If Trump is elected in November, it is going to fundamentally change everything I believe the United States has ever stood for and will set the country, and really the world, off in a profoundly uncertain and unstable new direction.

You don’t have to listen to me on this: Listen to Trump himself. I cannot recommend Time’s cover story interview with Trump from April enough. He simply tells you what he’s going to do.

The nut graph:

What emerged in two interviews with Trump, and conversations with more than a dozen of his closest advisers and confidants, were the outlines of an imperial presidency that would reshape America and its role in the world. To carry out a deportation operation designed to remove more than 11 million people from the country, Trump told me, he would be willing to build migrant detention camps and deploy the U.S. military, both at the border and inland. He would let red states monitor women’s pregnancies and prosecute those who violate abortion bans. He would, at his personal discretion, withhold funds appropriated by Congress, according to top advisers. He would be willing to fire a U.S. Attorney who doesn’t carry out his order to prosecute someone, breaking with a tradition of independent law enforcement that dates from America’s founding. He is weighing pardons for every one of his supporters accused of attacking the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, more than 800 of whom have pleaded guilty or been convicted by a jury. He might not come to the aid of an attacked ally in Europe or Asia if he felt that country wasn’t paying enough for its own defense. He would gut the U.S. civil service, deploy the National Guard to American cities as he sees fit, close the White House pandemic-preparedness office, and staff his Administration with acolytes who back his false assertion that the 2020 election was stolen.

Now, it’s possible that you are not alarmed by that paragraph, and perhaps you even agree with some or all of the plans Trump has in store. But you certainly can understand why many, many people—one might even say a majority, as the last two elections did—would be extremely unsettled and terrified by them. Trump’s signature skill, even before he got into politics, was division. My old Daily Illini colleague Kelly McEvers did a wonderful series for her NPR “Embedded” show about Trump’s pre-political life based on that premise, how his signature strategy has been to pit people against each other for his benefit. (Here’s an illustrative example about a Trump golf course and the American flag back in 2014.) I’ve written myself how Trump has specifically pitted families against each other. It’s something we’ve all experienced in one way or another. It’s why no one wants to think about this election: Who wants to go through all that again?

But Trump’s rhetoric, by design, is apocalyptic, end-of-days bombast: His “if we lose the election we won’t have a country anymore” bit is part of his stump speech at this point. A lot of people are taking that at face value—both those who support him and those who abhor him. It’s not difficult to understand why people feel unsettled. Someone is basing an entire presidential campaign—and, really, injecting himself, and this message of chaos, into every aspect of public life—on unsettling everyone and everything.

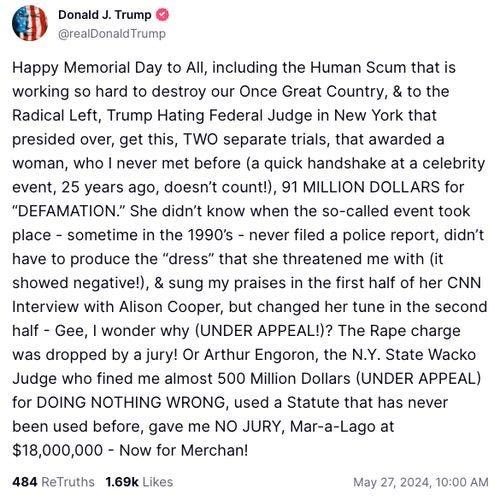

When the person who pushes that message, who says things like this on Memorial Day, of all days:

When that person is one of the two people who may be the leader of the free world in a few months … well, yeah, I think it’s pretty understandable that you, Robert, and many other people would consider this “a particularly unsettled time.”

So which is it? Are we uniquely imperiled? Or does it just seem that way?

I’m not sure I have the right answer to Robert’s question. That will not stop me from thinking about constantly—probably for the rest of my life, I’m afraid.

Here is a numerical breakdown of all the things I wrote this week, in order of what I believe to be their quality.

The Semi-Reinvention of Kyrie Irving, New York. He has changed a little in the last 16 months, but us? We’ve changed a lot.

This Week’s Five Fascinations, MLB.com. Chris Sale, dudes who walk more than they strike out, weird best players on every team, a silver lining for the Mets and what’s wrong with the Cubs?

The Best of Baseball in May 2025, MLB.com. The monthly roundup, currently on the front page of MLB.com.

The Ramifications of Ronald Acuna Jr.’s Injury, MLB.com. This is such a bummer.

This Week’s Power Rankings, MLB.com. The Cardinals are rising like a bullet. (Wait, I don’t think bullets rise.)

PODCASTS

Grierson & Leitch, Grierson is back from Cannes. We talk about the movies he saw there, as well as “Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga.”

Seeing Red, Bernie and I are suddenly enjoying this team.

Waitin’ Since Last Saturday, a pre-summer check-in with the fellas.

LONG STORY YOU SHOULD READ THIS MORNING … OF THE WEEK

“How Many No-Hitters Did Satchel Paige Throw?” Jayson Stark, The Athletic. I was heartened to see MLB’s decision to honor Negro League records and stats this week, though I only wish Josh Gibson had more hits than Pete Rose now, just to freak people out. But there are many complications with this whole project, and I trust no one more than Jayson Stark to sort them out.

ONGOING LETTER-WRITING PROJECT!

This is your reminder that if you write me a letter and put it in the mail, I will respond to it with a letter of my own, and send that letter right to you! It really happens! Hundreds of satisfied customers!

Write me at:

Will Leitch

P.O. Box 48

Athens GA 30603

CURRENTLY LISTENING TO

“King of Pain,” The Police. It’s funny that Sting used to be one of the most famous people in the world. The music is still good! Also, I still chuckle at Steve Martin’s joke when he hosted “Saturday Night Live” and Sting was the musical guest:

“We’re gonna have a great show, tonight’s guest is … [strains to read cue card] Stingy! No, wait … it appears that’s ‘Sting.’”

Remember to listen to The Official Will Leitch Newsletter Spotify Playlist, featuring every song ever mentioned in this section.

Also, now there is an Official The Time Has Come Spotify Playlist.

Hey, look what I filed to my editor this week:

The title is tentative. (Though I kinda like it.) But the draft is DONE. Bring me all the beers!

Have a great weekend, all.

Best,

Will

Early television was so powerful because for the first time people didn't need reporters telling them the circumstances. Reading about or seeing a photo of something never told the whole story. I think TV was the main spark of the civil rights movement. All of a sudden middle America was SEEING, in real time, black people beaten, attacked by dogs, blasted by fire hoses, etc, and realizing there's something seriously wrong going on down there.

Now? You can watch two video clips of the exact same thing and they're edited or spun to be exactly opposite, and most people will only believe their sources version of it. Every time.

If Biden can win in November and make it stick, because many Republican leaders have already signaled they will not accept the result if Trump is defeated, then I do feel somewhat more hopeful about energy and climate change than I have since I became aware of the issue. The Inflation Reduction Act has set a number of very useful programs in motion that will help to decarbonize our economy, especially in terms of leveraging public money to unlock private investment, but they will only be fully realized with a second Biden term.

We are only going to abandon fossil fuels when renewable technologies are less expensive. That has already happened with coal. It could happen with oil. It may be very hard to get there with natural gas. This may not result in a fast enough transition to avoid cooking ourselves, but it is as fast as we will go, so I hope it's sufficient. This is what passes for optimism round these parts. :)

I'm very pleased that you've finished your book, Will! Looking forward to reading it.