Volume 5, Issue 35: Marco Polo

"What are we, children? At our age it's enough surprise we're still alive every morning."

Here is a button where you can subscribe to this newsletter now, if you have not previously done so. I do hope that you enjoy it.

It is indulgent to go home. For the first time in more than two years this week, I went back to Mattoon, Illinois, the small rural town where I, and every generation of my family for more than 125 years, grew up. Like so many towns like it, towns that have been abandoned by industry—the only major employers left from when I lived there are the community college and the hospital—Mattoon is so different than it was when I last lived there in 1993 that parts of it are barely recognizable. But the foundation, the husk, is still there. The streets are the same. The high school hasn’t moved. You can still find a whole bunch of Leitches there. It remains my home.

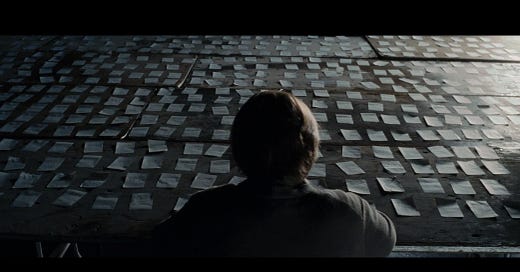

But it is always still indulgent to go back. You have so many roles as an adult, a parent, a spouse, a friend, a co-worker, a citizen, and these roles necessitate, in some ways, that you play a part—to place a little bit of yourself in storage so that you may perform what it required of you. The great Charlie Kaufman film Synecdoche, New York is about this idea, how you divide yourself up into so many different compartments, depending on whom you happen to be interacting with, on what role you are playing, that it can become confusing, even impossible, to figure out who you actually are. I try to be a good father, and trying to be a good father is something inextricable from my personality, but it is also, in its way, a mask I am putting on: I talk differently to my children than I do to an old friend I haven’t seen in years, or to one of my editors, or to my wife, or to my parents, or to the guy at the dry cleaners, or anyone. You can’t always be truly yourself. The world won’t allow it.

But when you are home, driving alone down old roads, walking through the parks where you used to play but haven’t visited in decades, conjuring up memories you had long ago forgotten you were supposed to remember, you are allowed to indulge—to return to the person you were years ago while trying to square that person with the one you have become. The stories that return are, essentially, interesting only to you. No one else could possibly care that the husband of Mrs. Burton, your first grade teacher, used to work at the old Icenogle’s grocery and always told you had an “Alfalfa cowlick” when you came in with your mom and would lick his hand and try to tamp your hair down every time he saw you. Mr. and Mrs. Burton are long dead; the only person on the planet who would even know, let alone care, that that happened at all is you. But you do know, and you do care. You do remember. It’s yours. It’s a little sliver of the vast history of this universe that belongs only to you.

Sure, it’s indulgent. But the desire to wade in its waters while you can is irresistable.

Much back home is still standing, after all, and the banality of what has endured holds its own power. There’s the old DMV, in the same place as ever, the roof yellowing, the parking lot cracking, with little shoots of grass peeking up through the asphalt. You’d been so nervous taking the test; the woman in the passenger seat never looked at you, just stared forward, “turn left here,” and you did, and you hoped you did it right because you wanted that license so badly, Homecoming was just around the corner, every other kid was picking up their girlfriends in their car, you better pass this test or it’s gonna be your mom dropping you off at your date’s house. When you returned to the building, there was a little bell that rang when you opened the front door, and you were so nervous that when it rang you jumped. The woman put her hand on your shoulder and whispered: “Relax. You passed. You did great.” You grinned and said thank you.

There’s that old house on the drive home, rusting but still standing, that always put up the miniature Ferris Wheel in their front yard as Christmas approached. It would light up and rotate all night, with little teddy bears in each little pod, as a figurine of Santa Claus, an old-time St. Nicholas version, the costume a little more brown and the beard a little thicker and more serious, stood on guard out front. I remember there being sheep too, for some reason. That’s how you knew it was Christmas time. The guy who lived there would put up the display on the Friday after Thanksgiving, and everybody on the road would follow, and then you could track your way home simply by following the line of them, sitting in the back seat, watching the lights flash by, nose pressed against the window. The house is still there, but it’s a different family now, and the Ferris Wheel is gone. It has been replaced by a TRUMP 2024 TAKE AMERICA BACK sign. You can follow the line of those home now too.

Then there is your old home, the one your father built with his bare hands when you were four years old because there was another kid coming, a baby girl, and he and Sally were going to need more room. He’d set you up a folding chair and a black-and-white television with rabbit-ear antenna, and he would actually build around you; there is an old picture of you surrounded by two-by-fours, your dad hammering as you fidgeted with Lincoln Logs. You grew up there, and your family lived there until Dad built another house, just across the road, and sold the old one to a kind woman who would later die in the front room—the same room where you watched the Cardinals win the 1982 World Series in, the same room where your mom told you your grandfather, her father, had died—leaving the house to an ex-husband who won’t sell it but also won’t take care of it. It has fallen into disrepair; the fence you dug the postholes for and helped dad construct has collapsed and rotted. You worry the foundation is sinking into the mud and that there are maybe wolves living in there now. You’re one of only four people in the world who know all that that house means, knows what was put it into it, knows its nooks and corners and all of its stories, and none of them live in town anymore. The only time any of that exists at all is when you visit.

It all comes back. It never really went away. But you cannot stay there. Not anymore.

I’m back home in Athens now, and I can already feel so many of those memories and feelings conjured up by spending two days in Mattoon starting to recede. I am needed here, after all. I have work to do, and people who need my attention, a future to build for that is more important than a past that exists, anymore, almost entirely inside my own head. It is my job to make the life I have here a stable place, one that my own children can return to in 30 years to luxuriate in their own memories, to indulge, to explore the person they were then and how that person connects to the one they have become. They will have their own stories that belong only to them, the ones they carry around, the ones that helped make them the person they will be, even if those stories only come back to them when they return.

And I will want them to return. They will need to return—and then go back to their lives to build whole new memories for their kids and all the people in their lives. And on and on it goes, for them, and for all of us. To revisit your past is vital, and even restorative: It’s memories, it’s nostalgia, but it’s also context, a framing to help us understand who we are, how we got that way and what we might bring to the world moving forward. Those memories may end up only mattering to us, and may in fact only exist within us. But that makes them more important to hold onto, not less. You do not want to live in your memories. But you don’t want the foundation sinking into the mud either. Our past is who we were. But it is, of course, also who we are. And who we will always be.

Here is a numerical breakdown of all the things I wrote this week, in order of what I believe to be their quality.

The Best Player at Every Age, MLB.com. It has been fun to watch this piece evolve every year.

This Week’s Five Fascinations, MLB.com. The Royals, Justin Verlander, The Best Team in Baseball, Manny Machado and the great Rich Hill.

This Week’s Power Rankings, MLB.com. I have enjoyed this as a bit of a weekly brain relaxer every week.

PODCASTS

Grierson & Leitch, no show this week, Grierson is at the Venice Film Festival.

Seeing Red, Bernie and I think the Willson Contreras injury should just about do it.

Waitin’ Since Last Saturday, we preview the Georgia-Clemson game, good times.

Morning Lineup, I didn’t do any shows this week. I’ve been in Illinois!

LONG STORY YOU SHOULD READ THIS MORNING … OF THE WEEK

“Why Trump’s Arlington Debacle Is So Serious,” Michael Powell, The Atlantic. Playing whack-a-mole with Trump atrocities is a fool’s game, but seriously, this one is particularly awful.

ONGOING LETTER-WRITING PROJECT!

This is your reminder that if you write me a letter and put it in the mail, I will respond to it with a letter of my own, and send that letter right to you! It really happens! Hundreds of satisfied customers! (I’m sorry I’m so behind on these. But I am starting to catch up!)

Write me at:

Will Leitch

P.O. Box 48

Athens GA 30603

CURRENTLY LISTENING TO

“Last Minute Shakedown,” Son Volt. The first band I go to when I’m back in Illinois, driving down country roads, is always, always Son Volt.

Remember to listen to The Official Will Leitch Newsletter Spotify Playlist, featuring every song ever mentioned in this section.

Also, now there is an Official The Time Has Come Spotify Playlist.

Very much enjoyed watching my Illini go 1-0 against those Eastern Illinois Panthers on Thursday. And I of course had to go see an old friend.

Have a great Labor Day weekend, all.

Best,

Will

Thanks, Will. You really can write. But more than that, you write with heart and dare I say soul. I am a lot older than you, but I can certainly relate to those old memories that are yours and yours alone. Thanks for helping us all look back today and see what shaped us, for good and ill, but shaped us nevertheless. Mattoon is a little larger than my 5,000 population hometown in West Texas but I can see myself so often in your reminiscences. Thank you for today.

Good story, Will. Even in a big city, with sprawling suburbs and the like, you see changes. The small town I (briefly) lived in nearly 30 years ago, isn't the same, either. The houses I grew up in, in and around Detroit aren't the same, either. (one isn't even there anymore) A few years back, I went to the cemetery where my maternal grandparents lay. I wanted to talk to my grandmother. The one, perhaps the only woman, who loved me unconditionally, in my life. It was a Sunday, though, and the office was 'for appointment only.' So, I never did visit her on the 50th anniversary of her death. Strange, how time is forever screwing with you. I was talking with my mother the other day, who's almost 88 and she said "you know, I'm just happy to be able to talk to my kids." She's outlived nearly everyone. Two husbands, her parents and most of her first cousins. I'm amazed myself because she smoked until her 60s. We're here for a few fleeting years and then we're gone and soon forgotten. But you remembering your first grade teacher and her husband is proof they live in memory.