Here is a button where you can subscribe to this newsletter now, if you have not previously done so. I do hope that you enjoy it.

If there has been one constant of my sportswriting career, which has now somehow lasted more than 25 years, it’s that people have always been arguing about Pete Rose.

When I worked at The Sporting News way back in 1998, the lowest staffer on the lowest rung, assigned to staying up until the late night NBA games were over and slapping headlines on them (“Blazers Scorch Sonics”) so they could be posted on AOL’s Website, a senior editor sent an email to the entire staff asking them to sign a petition he was putting together to censure broadcaster Jim Gray. Gray’s offense, in the eyes of this alleged journalist, was asking Rose, as he was coming off the field after being introduced as a member of MLB’s All-Century Team at the 1999 World Series at Turner Field, if he was ready to admit he bet on baseball. This was a pretty famous interview at the time, so much so that, two days later, Yankees outfielder Chad Curtis (who would later spend seven years in prison for sexually assaulting four teenage girls) would refuse to talk to Gray because of how he had treated Rose.

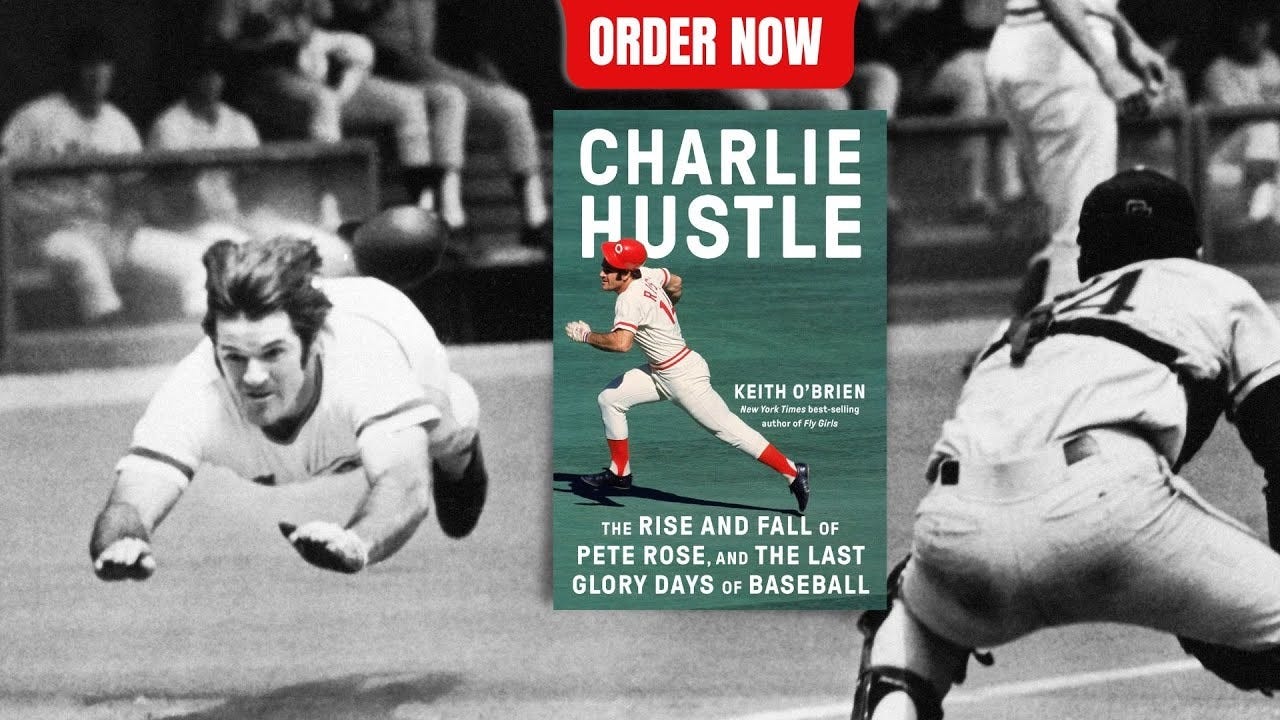

Even though I was a nobody at The Sporting News, I found it appalling, in that I’m-23-and-I’m-always-appalled-because-I-know-everything way, that someone whose job it ostensibly was to ask questions of people would be so angry at a journalist like Gray attempting to do that very thing, so I fired off an all-staff response to his all-staff email saying, and I’m paraphrasing myself here, “I found Gray’s questions entirely appropriate and don’t understand why any magazine journalist would be upset that he would ask them.” This email caused a whole kerfuffle of its own—it wasn’t a coincidence that I left the magazine to move to New York just a few months later—and I realized, for the first time, that Pete Rose was just one of those topics that you couldn’t discuss without having somebody’s vein pop out in the middle of their forehead. As I wrote in a review of Keith O’Brien’s fantastic Rose biography “Charlie Hustle” earlier this year:

Rose will always loom larger as an avatar for a very specific style of sports superstar, the undersized, scrappy almost-always-white underdog who defeats his athletic superiors through dint of hustle and relentless intensity—an ethos to himself. I see that Rose every time I watch a Little League dad scream at his kid to sprint to first base on a walk, every time a retired player lambasts a young (often Latino) player for showing too much “emotion” on the field, every time someone says they just don’t make baseball players like they used to. Deep down, they’re all talking about Pete Rose, the man who made everybody think, if they just hustled as hard as he did, they could play in the big leagues too. Rose is forever an ongoing baseball culture war.

Pete Rose died this week, at the age of 83, and I’ll confess, I fully expected his death to unleash one last cavalcade of these fights, everybody lining up in their corners and screaming at each other, like they do with everything else. We could all have our battles one last time. Pete should be in the Hall of Fame! They don’t make players like Pete anymore! He got railroaded by the media!

But, save for some very predictable exceptions, that’s not what happened. On the whole, Rose’s obituaries were not particularly equivocal. He was seen not the way that he saw himself, as the victim of endless conspiracies and a system rigged against him, but instead as the way he was: A once-inspirational hero whose reputation was slowly stripped to the bone as more and more people learned who he actually was. Pete Rose was a lot of things—a great baseball player, an incorrigible gambler, a relentless self-promoter, a forever aggrieved merchant of self-pity (he once wrote a book called My Prison Without Bars)—but in the end, there was one thing that anyone who had ever dealt with him in even the slightest passing way ultimately agreed upon: He was a miserable asshole.

There should be an emphasis on both of those words: Miserable, and asshole. He was definitely both. If you ever spent any time in Vegas, you’ve surely seen Rose at one of the card shows he was forever haunting, and no one ever looked more unhappy to be there: Rose’s snarl eventually developed into a hangdog look of defeat—it eventually just wears you down to a nub when you have to carry so much anger all the time. But what was most central to Rose was his vindictiveness and, crucially, his wanton disregard for other people. O’Brien’s book, which works hard to fairly and accurately show both why Rose was so beloved and also how his actions chipped that love down to nothing by the end of his life, details the myriad ways Rose was a monster to just about everyone in his life, from his teammates to his wives (and endless girlfriends) to his children to the people who worked for him and, ultimately, had their lives ruined by him. O’Brien, in the wake of Rose’s death, has been receiving messages about Rose from people who knew him. I found this one particularly indicative:

But the key thing to remember about Rose is not that he was a jerk. It’s that he was allowed to be a jerk. He knew he was being a jerk, and, throughout his life, because he was successful and glorified baseball player, no one ever made him stop being a jerk. O’Brien describes Rose’s single driving principle was “an enduring belief that his choices wouldn’t hurt him.” Early in his career, it became clear to Rose that not only was he an incredible baseball player, he was also representative of something to people that was larger than he was, that he wasn’t just a player but an ethos—a symbol to point to, an avatar of hard work and determination, or at least very specific demographic determinations of what that might mean. (Or, put another way, as one Philadelphia scribe penned at the end of Rose’s career: “White people need someone to root for too.”) What made Rose different is that he did not accept this as some sort of sacred responsibility, like many athletes before and after him, or even try to cut against it or undermine it as part of a larger project. He just saw it as something to exploit, capital to be used in his forever-project of narcissism and self-indulgence. (“All he cares about are baseball and Pete,” one of his many paramours told O’Brien.) Pete Rose believed he was untouchable, that he never had to apologize or change in any way, shape or form. One of the many tragedies of Rose’s life is that various baseball commissioners gave him countless off-ramps to get back in the good graces of the game, to apologize, to compromise, to negotiate, to settle. But he refused every time. Being Pete Rose meant never, ever backing down. This made some people admire him more. But there’s very little question that, at the end, it broke him entirely.

And it ultimately destroyed what had once made Rose so irresistible. I saw Rose play in person once, in 1984, in one of the 95 games he played for the Expos that year. (It was this game.) My father and I got there early just to see Rose. He was such a larger than life figure that it was hard to remember he was a real-life human being that you could stand 50 feet from, who took ground balls and stretched and tied his shoes. He was an epic figure who was near-universally revered. And then he spent the rest of his life whittling that reverence away.

And you saw it most clearly at the end. When Rose died this week, almost all that good will had vanished. In death, Rose got nothing he desired. He never made the Hall of Fame and there is no real groundswell of support for him anymore to get him there. Major League Baseball itself was mostly silent on his death; commissioner Rob Manfred said nothing, nor did Tony Clark, president of the MLB Players Union. Obits for Rose ended up focussing far more what he did to erode his on-field accomplishments than those accomplishments themselves. Rose was the all-time hits leader, of course, but he’s also first all time in games played, at-bats and plate appearances. Think about that. There is not a human who has ever existed who stepped on a Major League field more often than Rose, who took a bat to the plate more than he did. And when he died, that was the last thing anyone talked about. If anything: There was almost a sense of relief that we might, at last, no longer have to fight about him any longer.

It is a tragedy. But it is entirely a self-inflicted one. And I wonder if there is even some potential of, even hope for, ultimate justice for those public figures who live like Rose did—who saw in his obstinance a kindred spirit. Rose spent his entire life doing whatever he wanted, shoving aside anyone who stood in his way, betraying anyone who ever cared about him, being his worst self in service of only his own gratification, steadfast in the belief that there would never be any consequences for any of his actions. He did this so relentlessly, for so long, never apologizing, never backing down, that in the end, when he was laid to rest, like all of us ultimately will be, almost all of the good things in his life were forgotten, eroded by the inordinate self-regard that defined his time on earth. In the end, few stood up for him. In the end, there were consequences. In the end, he lost. In the end, he was alone.

Here is a numerical breakdown of all the things I wrote this week, in order of what I believe to be their quality.

Review: “Why We Love Football,” The Wall Street Journal. I wrote about Joe Posnanski’s new book. I’m a fan of Joe like everybody else is, but I’m not sure this book works.

Your Saturday MLB Postseason Preview, MLB.com. Doing these every day throughout the postseason. Here’s today’s.

Final Eight Rootability Rankings, New York. Carrying over from the annual Sweet Sixteen rankings.

George Clooney Movies, Ranked, Vulture. Updated with Wolfs.

The Top 50 Players of the Postseason, MLB.com. I do this every year.

The Postseason Power Rankings, MLB.com. With stakes for each team.

The Best of September, MLB.com. The last one of these this year, you see how it turns out.

Your Thursday MLB Postseason Preview, MLB.com. This just makes them a little moldier each day for this newsletter, though.

Your Wednesday MLB Postseason Preview, MLB.com. And a little more …

Your Tuesday MLB Postseason Preview, MLB.com. And yet somehow a little more ….

PODCASTS

Grierson & Leitch, we reviewed “Megalopolis,” “A Different Man,” “Wolfs” and “The Wild Robot.”

Seeing Red, Bernie and I went over a dramatic week in Cardinals baseball.

Waitin’ Since Last Saturday, we recapped that crazy Alabama game and previewed the Auburn game.

Morning Lineup, I did Friday morning’s show.

LONG STORY YOU SHOULD READ THIS MORNING … OF THE WEEK

“John Oliver Is Still Working Through the Rage,” Lulu Garcia-Navarro, The New York Times Magazine. An excellent interview with a guy I find increasingly essential. I cannot recommend this particular segment enough. Make sure to watch to the end, involving a segment about the parents of a boy killed in Springfield, which almost moved to me tears. (Click the caption to watch.)

ONGOING LETTER-WRITING PROJECT!

This is your reminder that if you write me a letter and put it in the mail, I will respond to it with a letter of my own, and send that letter right to you! It really happens! Hundreds of satisfied customers! (I’m sorry I’m so behind on these. But I am starting to catch up!)

Write me at:

Will Leitch

P.O. Box 48

Athens GA 30603

CURRENTLY LISTENING TO

“Runnin’ Down a Dream,” Larkin Poe. I’m very much loving the Tom Petty covers that make up the soundtrack of the Apple TV series “Bad Monkey,” which includes songs from The War on Drugs, Sharon Von Etten, Jason Isbell, Eddie Vedder, Kurt Vile, Charlotte Lawrence, Weezer and more. Check it out.

Remember to listen to The Official Will Leitch Newsletter Spotify Playlist, featuring every song ever mentioned in this section.

Also, now there is an Official The Time Has Come Spotify Playlist.

I don’t have video of it, but I was on “Morning Joe” yesterday morning talking baseball and promoting the “Morning Lineup” podcast. Had to wear my lapel pin to support.

Have a great weekend, all.

Best,

Will

Save that last paragraph to reuse in November

I guess the fine folks at Fox Sports heard the comments that “official baseball” had nothing to say about Pete Rose. Yesterday during the pregame show before the Mets-Phillies game, someone finally threw a sanctioned wake for Pete Rose which completely ignored the fact that his own conduct undermined the game he professed to love.

I was pretty disgusted when Fox hired Rose for their studio show. Although I’m not enamored of Alex Rodriguez getting such a prominent role on the network when he, too, blatantly disregarded the rules and disrespected the game through his years of steroid use and abuse, at least he has been contrite and he served his suspension. I may not like it, but he’s done his time. Rose, by contrast, was a consistent, unrepentant liar who never availed himself of numerous opportunities to not only admit what he did but to apologize for his gross misconduct of betting on baseball. For Fox to glorify Rose and simply pretend that he did not receive - and agree to receive! - a lifetime ban from baseball is appalling. When he was on the air, I had to shut it off.

Gambling is obviously everywhere now - I get that. But that does not retroactively exonerate Pete Rose. Major League Baseball Rule 21, when Rose played and still today, prohibits betting on baseball, including legal betting. And why? Because it undermines the integrity of the game. Fox should never have aligned itself with Rose, and in my view, because he violated one of the most fundamental rules of the game, he should not be honored with induction into the Hall of Fame, regardless of his accomplishments.