Here is a button where you can subscribe to this newsletter now, if you have not previously done so. I do hope that you enjoy it.

Working in the media industry as I do, I am very familiar with what it feels like to be laid off. (I wrote a whole piece about it last year.) Whenever I talk about being laid off, I can’t help but write from the perspective of today, when it all (for now) turned out for the best, centering what happened in the end, the valuable lessons from the experience, how I discovered my true value and purpose by refocusing on what I did well and what I had to offer rather than whatever hoops I may or may not have been trying to jump through at a particular job that wasn’t the right fit in the first place. All that is in fact true, but whenever I tell the story like that, it skips over another important aspect of getting laid off: The short, and important, period immediately afterward when you turn into a complete and total slug.

This is a normal period, and a sane one: We get so caught up in the day-to-day stresses of our jobs that when that job is taken away from us, whatever long-term worries we may have, it is refreshing, even freeing, to get unplug and zombie out for a little while. It’s a decompression period, and an all together healthy one. Some people catch up on television shows they always wanted to get around to; some people plunge into reading; some people travel. It’s good for you, even rejuvenating, preparing you for the next challenge, whatever is waiting for you next.

It has been a long time since I have been laid off—12-plus years, and even then it was just one of the two jobs I had at the time that went away; the last year I spent any time officially unemployed was 2003—but it happened often enough back then, in a compressed period of time, that I established for myself a clear coping mechanism: I played video games.

Specifically: I played NBA video games.

I humbly submit to you that I am one of the greatest players of NBA Live 2004 that has ever lived. I had that game mastered. My good friend Mike Bruno was another common media casualty of that era—he ended up landing on his feet—and we spent a full month back then spending the first half of every day sending out resumes and the second half playing out a convoluted but intricately detailed massive NBA Live tournament against each other, which I vividly remember ending with my Lakers wiping out his Michael Jordan-led Washington Wizards in a four-game sweep. I honed my skills to a fine point back then. I was particularly skilled with that particular Lakers team, because it was a superteam at every premium position: They had Kobe Bryant and Shaquille O’Neal, of course, but they were joined by two Hall of Fame ring chasers who had been fixtures of the game for years: Point guard Gary Payton and power forward Karl Malone. I dominated with that team. I can still remember having Payton bring the ball up the court, tossing it down to Malone in the post and either dumping it in to Shaq or hitting a slashing Kobe for a dunk. I—unlike that actual Lakers team—could not lose.

That was the last period of time, a time when it was just a relief to get to vegetate for a bit, that I could ever play video games regularly enough to consistently beat them. I am not generally good at video games and, other than those periods of unemployment 20 years ago, have never spent much time playing them. You know how it goes: There’s always some kind of work to do. (Particularly when you’re trying to write a book while doing your all your regular daily jobs as well.) I do sometimes miss playing video games. But I would miss working a lot more. Besides: I’ll always have NBA Live 2004. No one was ever better.

But these days, there’s one week a year in which I actually have some time off, when I try to unplug a bit, when I, for once, try not to work too hard. It’s the week between Christmas and New Years. I read more. I sit down and write letters to people. I try to sleep a little later. And yeah: I like to play some NBA video games.

The difference now is: I don’t need a fellow recently laid off media casualty to put together a big tournament with me. Now I have a 12-year-old who lives in this house. He’s very handy that way.

So this last two weeks, my son William and I have had a nightly appointment to play NBA2K24. We drafted 16 teams in a single-elimination tournament, headlined by his Bucks and my Knicks. We scheduled the whole thing out, and we imagined it being hard-fought, tightly contested and, more than anything, a bonding experience.

And he smoked me. I mean he smoked me. I won three games. He won 14. And I’m pretty sure he let me win those three because he felt bad. I’m not sure there’s a worse feeling for a father than his 12-year-old openly pitying him.

So what happened? Part of it is the natural reflexes of a 12-year-old against a 48-year-old. William isn’t given free rein to play the Xbox whenever he wants, but he plays it more than his father does, and it became clear, quickly, that the game is more designed for the way he receives input from the world than the way I do. When I played the game in 2003, there were four buttons: Jump, shoot, pass and run, and you only had to pay attention to the guy dribbling the ball. Now, there are twice as many buttons, and because you can push two particular buttons at the same time and make your player something entirely different than you would do if you just pushed one, there are roughly 64 different movements to keep track of. (For some reason, I kept pushing the button pattern that makes your player suddenly smash the ball against the court as hard as he can, sending the ball flying out of bounds. Why does the game even have that movement?) There are also countless things flashing across all different corners of the screen constantly, none of which I understood or could focus on anyway but which William was able to absorb and exploit effortlessly. He ran one play where three of his players converged on one of mine, who was so befuddled that he stopped dribbling and just handed the ball over, like it was money he owed to them. I think at one point I saw my shooting guard start crying.

It had been many years since I threw a video game controller across the room. I broke that streak last week.

So yeah: I’m not as good at video games as a 12-year-old. The larger problem, though, is one that’s bigger than just a video game. After a while, some of my old muscle memory returned, and I remembered how I used to play, what used to make me so good. I’d dump the ball into my power forward, he’d dribble around a bit, then he’d try to get in solid post position to score, just like Malone (and Tim Duncan, and Alonzo Mourning) did in 2003. This strategy allowed me to score at a pace roughly similar to how I scored against Mike Bruno back in the day. I went with what worked for me in the past, because in my mind, when I start playing, it is 2003. I’m the same guy. Nothing has changed.

But everything has. While I was playing 2003 style basketball, William was playing 2024 basketball, which is to say: He was passing the ball around the perimeter, constantly, waiting for a 3-point shooter to get open and then draining the shot when one did. He did this because this is how basketball is played now. The analytic revolution in the NBA has discovered that the most efficient way to score (and win) is not to play the sort of post-oriented “fundamental” basketball that was in vogue when I played NBA Live in 2003; it’s to maximize 3-point opportunities. This shouldn’t be revolutionary—it turns out that analytics’ blinding insight was “three is more than two”—but it has changed the NBA in dramatic ways, turning much of the league into Stephen Curry wanna-be clones. And thus there are so many more points now. If you’ve watched an NBA game in the last five years, you already know this: As Tom Ziller pointed out in his fantastic newsletter this week, the six best, most efficient offenses in NBA history are playing right now, this season. The game is just different.

William has internalized this. He does not know, or care, about the analytics, or what the game used to be like. He just watches the NBA, sees how they play and constructs his offense gameplan accordingly. This, to him, is not only natural, it’s the way things have always been. The problem is not with the way the game is played now. The problem is that I remember it differently. Which, you know … who the hell cares what I remember? The game moves on regardless. If you don’t want to get with the program, well, feel free to go ahead and lose.

Which I did. Repeatedly. That’s the worst part. I saw the way William was playing. I saw that it was a better way of playing than I was playing. I saw I would never beat him if I kept playing like I was. But I did not stop. I did not adjust. I did not change a thing. I just kept tossing it into my power forward, like I did in 2003, trying to make the world the way I wanted it to be, rather than the way it actually was.

But I don’t have the power to actually do that. The world is different. I refused to get with the program. So I lost. Over, and over, and over.

There is a whole political movement in this country that is not based in ideology, or principle, or any sort of altruistic notion of what is best for all of us. It is simply: Things have changed. I do not like that. Rather than alter anything about myself, or attempt any meaningful personal growth, I will stomp my feet and scream that everything must return to the way it was when I was personally most comfortable with it. It is the world that is wrong, not them. They have hit a point in their lives that they have decided they no longer want to learn about the world outside of their own experience. Not just that: They also demand no one else learn either.

As I’ve gotten older, this seems more and more the fundamental question facing almost everyone I know and, in many ways, the fundamental question of a terrifyingly pivotal 2024: Can you handle change? Change not just in the world, but within yourself. I see people accepting the world as it comes to them, trying to educate themselves, to empathize with people different than them, to improve. And then I see a bunch of people throwing the controller across the room.

Here is a numerical breakdown of all the things I wrote this week, in order of what I believe to be their quality.

How Michigan Became College Football’s Unlikely Villain, New York. I am sorry to all my friends who went to Michigan for writing this!

Eight Things We’re Looking Forward to in 2024, MLB.com. I was actually on MLB Network discussing this piece this week.

You can watch that full segment right here.

What This College Football Season Meant, CNN. Gonna be writing a bit more often for CNN this year.

Remembering Baseball People We Lost in 2023, MLB.com. My annual In Memoriam piece.

Matt Chapman Free Agent Power Rankings, MLB.com. I still think the Giants should get him.

I Wrote the First Power Rankings of 2024, MLB.com. The NL Central is very weird right now.

PODCASTS

Grierson & Leitch, no show until mid-January, but you should listen to Dorkfest again.

Waitin' Since Last Saturday, we recapped that Orange Bowl massacre.

Seeing Red, we did a end-of-year wrapup.

LONG STORY YOU SHOULD READ THIS MORNING … OF THE WEEK

“We are different from all other humans in history,” Brian Klaas, The Garden of Forking Paths. This has quietly become a constant can’t-miss read for me.

Also, definitely read this from my old editor Tom Scocca.

ONGOING LETTER-WRITING PROJECT!

This is your reminder that if you write me a letter and put it in the mail, I will respond to it with a letter of my own, and send that letter right to you! It really happens! Hundreds of satisfied customers!

Also, every single one of you who sent me a holiday card is incredible.

Write me at:

Will Leitch

P.O. Box 48

Athens GA 30603

CURRENTLY LISTENING TO

“Honk If You’re Lonely,” Silver Jews. I have been obsessively listening to Silver Jews since the start of the year. Sad, lovely, January music. It’ll be five years this August since we lost David Berman.

Remember to listen to The Official Will Leitch Newsletter Spotify Playlist, featuring every song ever mentioned in this section.

Also, now there is an Official The Time Has Come Spotify Playlist.

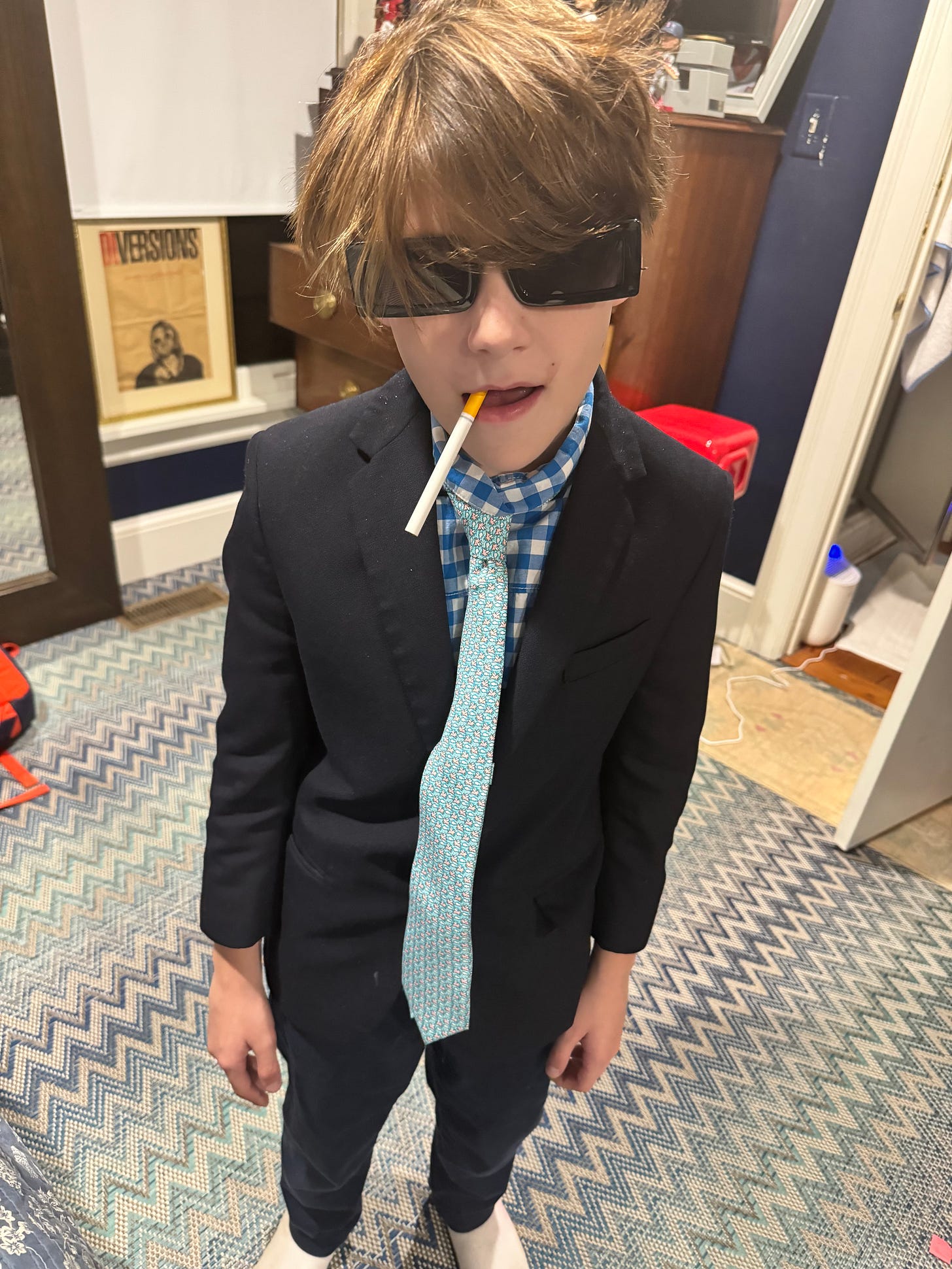

Welcome to 2024. Look what it has done to poor Wynn already.

Have a great weekend, everyone.

Best,

Will

Love this. So relatable, and so true: the crux of the issue is people's reluctance/refusal to change. Tom Scocca's story is harrowing.

Well played Will.