Volume 5, Issue 5: In Camelot

"You want in a real game, I'll hook you up. High stakes, exclusive clientele. David Lee Roth."

Here is a button where you can subscribe to this newsletter now, if you have not previously done so. I do hope that you enjoy it.

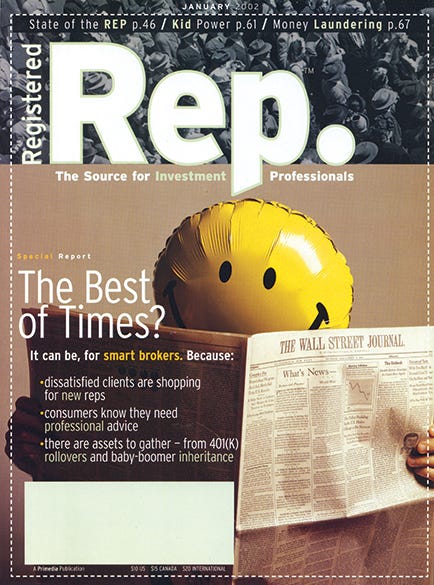

My first full-time reporting job, with benefits and everything, was at Registered Rep. magazine. It was 2002, we were owned by a newspaper conglomerate, I took the A train from 207th Street to 14th Street to go in the office every morning, enough time to read the Daily News cover to cover, there was a New York Sports Club right next door that gave discounted memberships to everybody in the building, there was an Irish pub across the street we all drank at all night after we closed an issue. It was a real job. Registered Rep. covered the financial services industry, a trade publication for stockbrokers, and my beat was the regional brokerages: Raymond James, Edward Jones, A.G. Edwards, Charles Schwab. I was expected to cultivate sources at each of those regional brokerages, talking to brokers every day, getting a sense of the trends in the industry, their individual complaints, the way the wind was blowing. I talked to brokers to write about brokers for brokers.

I was not good at this job, for the reason I’m not good at most of the things I’m not good at: I didn’t really care. I cared about doing my job, and I really did do my best, but at the end of the day, I just didn’t really care about regional brokerages in the financial services industry and, no matter how hard I tried, simply could not talk myself into doing so. I needed that job, though, so I was able to stick around, partly because I was a competent enough writer to fake it when I needed to and mostly because I loved my editor. Registered Rep.’s editor was a man named David Geracioti, a whirling dervish of a man who had studied philosophy at the University of Michigan before going to grad school in journalism at NYU. David was intelligent, manic, funny and mercurial: He was the kind of editor whose energy was so bottomless and passion so boundless that you worked hard just to match him—it meant so much to him that you wanted it to mean that much to you, even if it didn’t. David loved my writing but hated my reporting, could not understand why I couldn’t understand basic concepts of the financial services industry; I once spent an entire afternoon with him at a sports bar, watching his Wolverines stomp my Illini, as he mapped out complicated investment strategies on bar napkins. I didn’t understand what he was talking about, but it was hypnotic to watch him: I’d follow him into hell, or at least the offices of an A.G. Edwards advisor in a strip mall in suburban Tulsa, whichever was worse.

Eager to rev me up, David decided on some immersion therapy: He would send me to cover a national Charles Schwab conference in Las Vegas, where I’d live amongst the reps, mingle with them, drink and gamble with them, truly understand their stories. I’d be out there a week, and I was expected to file two stories every day: One a nuts-and-bolts rundown of the day’s conference events, and one a profile of an individual broker, their goals, their hot tips, their worries, their hopes, their fears. He booked me a flight, got me a room at the MGM Grand and even gave me the company credit card—the first credit card I’d ever had in my life. “Go find some stories,” he said, trying, as always, to sound like Raoul Duke, he loved Hunter S. Thompson, “buy the ticket, ride the ride.” It was a real work trip. To Las Vegas.

The first thing I did was call my dad. My father loves Las Vegas, will find any excuse he can to go there. He is not a heavy gambler and has never been attracted to Las Vegas for its vice; he usually would go with his mom or his wife. Dad is a cautious, rational gambler, one of those guys who will play for hours but never bet more than $10 a hand; at the end of a week in Vegas, he’ll be up $1,000 and gotten his room comped, I have no idea how he does it. Las Vegas has always represented escape for him, a place in the desert that was far from home but also familiar, where the unexpected was around every corner but still something you could see coming, if you played your cards right. It also represented achievement for him: A reward for all your hard work, a place where, if you could get there, an electrician from rural Illinois could walk the same halls as Sinatra and Elvis.

I couldn’t wait to tell him: I’m going to Vegas! For work! Come meet me! He booked a flight the next day. I wanted him to be proud. I had a real reporting job, finally, and they were sending me to Vegas. I even had a free hotel for him.

He arrived about three hours after me. I’d spent the afternoon listening to guys named Gary and Lloyd complain about their regional managers, writing down every word they said like the Pentagon Papers, and then I met Dad for an early dinner. I’d been in New York City for almost three years at this point, and still hadn’t gotten my head above water, financially; I could only afford to go home for holidays, so I really only saw my father a couple of times a year. He was looking older, I thought. His goatee was speckled with gray, and he groaned a little when he got out of his chair. The mother of one of my closest friends had died the year before; I was acutely aware, as much as any twentysomething can be, of the increasing frailty of parents. We had a beer. Dad asked me what I was planning on writing about; I told him I had no idea. There was a Charles Schwab mixer that night—one of those mixers where everybody mills around an unused dance floor drinking vodka tonics as the DJ plays “Play That Funky Music,” like, five times—and I had another conference to cover the next morning at 8 a.m., so I told him he was on his own for the night, that’d I’d just go up to the room and crash. He told me not to wait up, he’d be fine, he’ll be at the blackjack table.

I went to my event, talked to some more Garys and Lloyds, heard Sugar Ray’s “Every Morning” a few times, then went back to my room. Dad was not back yet, so I left the bathroom light on for him so he could see when he came in. I fell asleep. At 2:30 in the morning, I woke up, leaned over and saw my dad’s bed still empty. Where was he? I checked my phone; he hadn’t called. Had something happened? Oh God, I’d heard stories of older people developing blood clots on long flights that lead to an unexpected stroke. Had Dad had a stroke? Was he in some Vegas hospital, alone, and no one knew to get a hold of me? I began to panic. I put on my clothes and a baseball cap and headed down the lobby. Maybe the front desk had heard something? It’s 2:30 in the morning. Why isn’t he in bed?

I dragged myself into the elevator, hitting the wrong button three times, and stumbled out onto the casino floor. I practiced what I’d say. I’m sorry to be a bother, I know this sounds strange, but my father was supposed to be in his room and he’s not and I don’t know where he is, have you perhaps had any middle-aged men have strokes this evening? My eyes bleary, lights flashing and blinking all around me, I made my way toward the lobby. I then heard a voice from to my side.

“Will! Hey, Will! What are you doing up?”

It was my dad, sitting in the exact same spot at the exact same table he was when I’d seen him last.

“Jesus, you’re still here?” I said.

“Why wouldn’t I be?” he said, big toothy smile on his face. “I’m up 200 bucks!”

“Good night, Dad,” I said, trying not to growl at him.

Upstairs, I stayed awake, staring at the ceiling. Nothing had happened. Dad was fine. Of course he was fine. But someday maybe he wouldn’t be. I had never thought about my dad getting older, or being sick, or maybe someday not being there. For the first time, in that Vegas hotel room, I’d had to confront that I was worried about him—that I was scared I might someday lose him. That panic was unnecessary, probably silly, but also very real. I was the child nervous about the parent, rather than the other way around. When would I get to go to Vegas with him again? Why was I spending this time talking to Gary? My Dad is right here.

I skipped the next day’s conference. I ended up oversleeping. I filed a junky, filler story to my editor David, and spent the day watching baseball with Dad, betting 10 bucks on the Cardinals to win just so we could sit in the sports bar all day. He didn’t look old anymore. He just looked like my dad. The Cardinals won. We cheered.

My editor called me the next day. “Your story was terrible,” he said, but he sounded amused. “You’re getting the true Hunter Vegas experience, seems like. Too weird to live! Too rare to die!”

That was 20 years ago. My dad was in his early ‘50s then, just a little bit older, actually, than I am now. He is more frail now than he was then, but hey, so am I, so are all of us. This week, I’m traveling to Las Vegas again for work, this time to cover the Super Bowl: My 12th, if you can believe that. As soon as I knew I was going, I called my dad. I’m going to Vegas! For work! Come meet me! So I’m flying out there Tuesday and he’s flying out there Saturday, and we’ll have dinner and he’ll stay up too late, though not as late he used to, and I’ll worry about him and I’ll appreciate every second I’ve got with him because we can still go to Vegas, where an electrician from rural Illinois can walk the same halls as Sinatra and Elvis.

I will appreciate every minute of it. You never know when it’ll be gone. In early 2005, after two years at Registered Rep., I walked into David’s office and told him that I was appreciative of all he had done for me but it was time for me to go; I had a sports website I was going to try to launch. He wished me luck. “You were a terrible brokerage reporter,” he laughed, “but we had some fun, didn’t we?” He put a pen in his mouth and jutted it out like a cigarette holder. “You can’t stop here! This is bat country!”

When my career finally got some traction in the years after I left Registered Rep., David would always send me kind notes about my work, telling me he was proud of me, usually with Hunter quotes, and he’d taunt me every time Michigan beat Illinois at something, which was often. I was always happy to hear from him. Then, a few years ago, I heard from one of my old co-workers; David had died suddenly, at the age of 54. I hadn’t realized he was that young. Our bosses always seem older than they really are. He would have loved Michigan’s championship last month. He always thought Harbaugh would get them back there.

Las Vegas is not my kind of town. I will write some stories, I will eat some good food, I’ll watch some sports, I’m gonna splurge and go see U2. Suffice it to say, though: The type of person who makes a pilgrimage to Las Vegas the week Las Vegas is hosting the Super Bowl is not necessarily my kind of person. But there is value in the fact that Las Vegas is simply always there, a place to make memories, to hold onto other ones, to have as a destination where you may gather with those you have been away from for too long. I try not to panic about losing the people closest to me anymore. I just try to hold onto the time I have with them, and be grateful. This is the life we have, after all, and we only get to do this once. We'd be fools not to ride this strange torpedo all the way out to the end.

Here is a numerical breakdown of all the things I wrote this week, in order of what I believe to be their quality.

Dan Campbell and the Lions Were Right to Trust Math, New York. I can’t believe we’re still having these debates.

Ranking Potential World Series Rematches, MLB.com. Hey, let’s do 2006 again, I love Detroit, they deserve a World Series after what happened to the Lions.

PODCASTS

Grierson & Leitch, Grierson’s back from Sundance, and we discussed his favorite film from the festival, Jesse Eisenberg’s “A Royal Pain.” We also discuss Robert Altman’s “California Split” and “The Man in the Moon,” Renee Zellweger’s first film.

Seeing Red, no show this week.

LONG STORY YOU SHOULD READ THIS MORNING … OF THE WEEK

“To Stop a Shooter,” Jamie Thompson, The Atlantic. I cannot stop thinking about this story.

Also, this Sam Miller piece about Mike Trout is terrific.

ONGOING LETTER-WRITING PROJECT!

This is your reminder that if you write me a letter and put it in the mail, I will respond to it with a letter of my own, and send that letter right to you! It really happens! Hundreds of satisfied customers! I am caught up on anything sent in 2023 now, so if you haven’t gotten a response, it got lost, send me another one!

Write me at:

Will Leitch

P.O. Box 48

Athens GA 30603

CURRENTLY LISTENING TO

“Under Cover of Darkness,” The Strokes. I used to be a pretty big Strokes skeptic, and now that it’s years later, I think it’s just because of how they looked; I felt like a schmuck liking a band like that too much. Now I can just listen to the music. The music is good! I particularly enjoy songs with dueling guitars like this one, in which case two guitarists seem to be in conversation with each other. “Impossible Germany” is the zenith of this sort of song, but this one’s great too.

Remember to listen to The Official Will Leitch Newsletter Spotify Playlist, featuring every song ever mentioned in this section.

Also, now there is an Official The Time Has Come Spotify Playlist.

Got my best half-marathon time last week, which was good, but have been barely able to walk since, which is less good but still kinda worth it.

Have a great weekend, all.

Best,

Will

Congrats on your half-marathon time. Have a great Vegas trip. I saw U2 twice at Sphere last year and it was great. Also not much of a Vegas guy. This last trip especially made me feel out of place there.

This is my 25th year living in Vegas. The desert agrees with me, health wise, but this town also gets in your blood. If you can enjoy its spoils in moderation, you can live a pleasant life here.

The strip, however, is absolutely ridiculous nowadays. LV corporate greed knows no boundaries. This clip speaks volumes about how things are here now.

https://youtu.be/HUt--DZuW3Q?si=7OBKlRKmOmiJyWuj